A week ago Friday, I presented on a panel at the 2025 Conference on American History, held by the Organization of American Historians in Chicago. For someone who dropped out of graduate school without even getting a masters’ degree, this felt like quite the intellectual accomplishment, to be invited to present alongside Real Historians.

The panel I was on was titled “David Montgomery’s Working Class: Reconsidering a Labor Historian’s Legacy.” The panel abstract lists a whole bunch of questions about Montgomery’s academic work that were, to be honest, a bit above my pay grade — and, truth be told, while I read and reviewed a recent, posthumous collection of his essays for the UE NEWS, I haven’t read the majority of his writing.

But I did feel like I could address the final questions listed, about his life-long connection to the labor movement1 and to popular struggles, and how that engagement provides a model for how intellectuals can make their work relevant to the public and to workers in particular. I did some research in the primary sources — reading through the four addresses that Montgomery gave to UE conventions between 1966 and 2009 in the convention proceedings — to give an overview of how he took advantage of that opportunity to help union members connect the struggles they go through in their daily lives to broader historical forces, and to see themselves, and the working class more broadly, as not just subjects but agents of history, who can shape those historical forces as well as being shaped by them.

As it turned out, this question about intellectuals making their work relevant to the public would be far more pressing than I could have imagined it would be when the organizers submitted the panel proposal last spring.

I arrived in the City of Broad Shoulders on Thursday afternoon a bit out of sorts for reasons completely unrelated to the conference. I hadn’t originally planned to go to the opening-night plenary, on “The United States Constitution, Past, Present, and Future,” but as I checked in and got my name badge and everything I thought maybe I should, if only to take my mind off of other things.

But when I opened the program, a paper addendum announced that the plenary on the constitution had been rescheduled for Friday night; its opening-night slot had instead been hastily reallocated to a new plenary on “Historians and the Attacks on Education.” (So hastily that the name of one of the most prominent historians on the new plenary, Nancy MacLean, was misspelled as “Nancy McClean.”)

The new session did what an opening plenary should, which is set the mood for the whole conference — though in this case, it was perhaps more of a recognition of the mood that would have prevailed anyway.

As one might expect at a conference of historians, the room — and the conference as a whole — was filled with a lot of middle-aged white men with well-trimmed beards, slightly socially awkward but personally confident, wearing button-down shirts and in a few cases jackets, but no ties.

In what was perhaps a sign of loss of confidence in the relevance of the historical profession, or in its ability to defend itself against political attacks, two of the panelists were not even historians — one an advocate for equity in public schools, the other a former chair of the Ohio Democratic Party. They offered perfectly fine but hardly revelatory political advice.2

MacLean, one of the foremost scholars of the American right, broke down the historic “tripod” of the right wing: predatory capital, white supremacy, and evangelical Christianity, and outlined how each of these sectors has become both more aggressive and more desperate in recent decades. She pointed out that the reason the Trump administration is acting so quickly (and, I might add, relying so heavily on executive authority) is because the right wing is, in fact, scared, and realizes that this may be their last chance to impose their agenda, which is actually quite unpopular, on a wildly diverse country.

Leslie M. Harris, of Northwestern University, reminded the audience that the advances made by women, people of color, and other marginalized groups within academia are in fact quite recent, and quite fragile — and came about only because of struggle. Even the expansion of higher education to non-elite white men with the G.I. bill happened less than a century ago, and decades of austerity imposed on public colleges and universities have made higher education less and less accessible in recent decades — and thus an easier target.

In response to a question from panel chair and OAH President David W. Blight about whether the profession, or perhaps the academy more broadly, might have done something to bring these attacks on itself, Johann Neem of Western Washington University spoke about how his parents had immigrated to America to pursue the “American Dream” during a period which he called “the regime of equality,” and vaguely suggested that identity politics (though he pointedly avoided using the actual words “identity politics”) had in recent decades undermined that regime, and thereby contributed to the backlash against academic history. Both MacLean, who is white, and Harris, who is Black, vigorously rejected this suggestion. The two white guys on the panel, the non-historians, kept their mouths shut.

That was about it for strategic debate. Harris made some caustic and on-point comments about the weaknesses of the Democratic Party, and MacLean, referencing the 1979 film Norma Rae, held up her program booklet above her head and urged people to join their union, the American Association of University Professors. But no one addressed what seems to me is the $64,000 question in this moment: how to articulate a vision of higher education (and, for that matter, scholarship in general) that is relevant to the public, and to the working class in particular.

Before David Montgomery became an historian, he was a machinist. He worked at Premier Machine, a small machine shop in Greenwich Village, and he was the shop chair for UE Local 475, once one of UE’s largest locals with over 20,000 members in multiple shops around New York City.

But he wasn’t uninterested in history. During his time as Local 475 shop chair, he persuaded the local to invite W.E.B. DuBois, the great Black historian, civil rights activist, and all-around public intellectual, to address one of their meetings.

Local 475 was also the home local, some years earlier, of UE rank-and-file activist turned staff organizer Ralph Fasanella, who quit his job as an organizer to paint, and was eventually recognized as one of the greatest “outsider” artists of the 20th century. I’ve been reading Fasanella’s City, a book-length 1973 profile of Fasanella and his art by Patrick Watson.

According to the interviews in the book, part of the reason Fasanella quit his job as an organizer is that, during World War II, he saw the labor movement (even UE, the left wing of the CIO) turning away from a borad vision of liberation, one in which working people would be not simply be less oppressed but able to fully develop their potential, towards more economistic goals, of just better pay and benefits. Not that Fasanella didn’t value the better pay and benefits that he helped workers win — but in some perhaps inchoate way, he wanted to fight for more.

“For a working guy to grab a bit of knowledge in this society, it’s a rough ball game, a rough one,” Fasanella told Watson.

Although I dropped out of graduate school over a quarter of a century ago, I do try to keep up with the field, and periodically attend conferences of the Labor and Working-Class History Association. (In fact, I will be presenting at the 2025 LAWCHA conference in Chicago in June.) So at LAWCHA conferences I tend to know people, or if I don’t know them personally, I am familiar with their work and can strike up a conversation — and, of course, at LAWCHA conferences people are often interested in talking to a trade unionist, even if they don’t know me.

Turns out that, unsurprisingly, all of those things are much less true at the OAH. As a result, I spent a fair amount of the conference feeling somewhat awkward and lonely, drinking coffee or beer by myself, and eavesdropping, as one often does in such situations.

The mood among the rank and file, as it were, was even more confused than the mood of the opening panel. A professor at a public university that I know to be unionized was exasperated but deflated at being told by a provost in one breath that the administration has no intention of censoring faculty, and in the other breath that they want to make sure they don’t get sued. As an example of an action that might get the university sued, the provost suggested that faculty should avoid challenging any students who claim that the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery. The professor seemed to have little idea what to do.

More than once I overheard some variation of Blight’s question from the opening plenary, “What did we do to bring this on ourselves?” The most common answer people gave each other was along the lines of “failing to defend our basic values and principles.” But I never heard any discussion of what those basic values and principles are. (I guess, as in any in-group, everyone just sort of assumes that everyone agrees on basic values and principles). There was a lot of disappointment in university leadership — “I’m not seeing anything I want to see from a university leader right now,” “this is not million-dollar leadership” — but little discussion of where alternative leadership might come from.

On Saturday morning, two of those middle-aged white men with well-trimmed beards were chatting about the situation. One said he planned to skip the 11:45 block of panels to attend the local “Hands Off” march because “I just need to be with people.” The other related that at dinner the night before, a senior colleague had gathered everyone’s attention and queried: “I have a question I have to ask: What is to be done?” If his dinner companions came up with any answers, he didn’t share them.

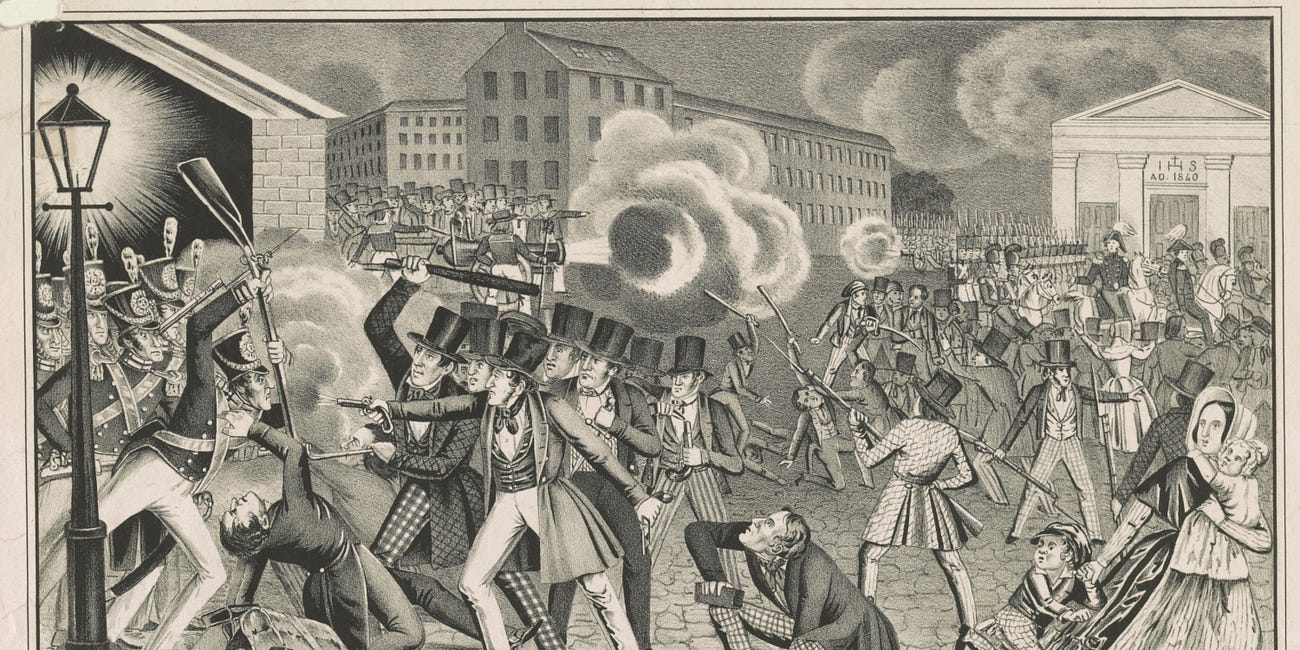

History presents a complicated target for the right wing. Unlike more analytic disciplines, where whole categories of analysis can, in theory, simply be scrubbed from practitioners’ vocabularies under the banner of removing “DEI” or “wokeness,” the existence of the past, and of a past that contains women and Black people and slaves and masters and workers and capitalists, is extremely difficult to simply wave away. In that sense, history cannot simply be denied, it must be rewritten. (Those students who deny the relevance of slavery to the Civil War have to come up with — or be fed — some reason why so many Americans took up arms against each other in the bloodiest war in our nation’s history, after all.)

But in another sense the right-wing efforts to make history bend the knee are a denial, not of the existence of the past, but of the existence of historical processes, or at least their relevance to the present. The fear that is a crucial part of right-wing authoritarianism is an unreliable tool — people can always overcome their fear, especially when they gather in tens of thousands in the streets, when they find ways to be with other people in their fear and confusion. Far more effective is instilling a sense of inevitability, a certainly that change may have been possible in the past but is no longer, that the Thousand-Year Reich is upon us.

And the people who, at least in my lifetime, have been most successful at this kind of denial of history are the neoliberals who insisted that “Western liberal democracy” was the final stage of human development —Margaret Thatcher’s “there is no alternative” became Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history” within a decade — and that Western liberal “democracy” demanded absolute obeisance before the authoritarianism of the market. The market whose victims have, time and again, in country after country, provided the margin of victory to the right wing.

Friday night, after a few drinks at the bar with a facilities manager from Georgia Tech, I poked my head into the end of the rescheduled plenary about the constitution.

The featured speaker, Jeffrey Rosen of the National Constitution Center, was working himself up into a remarkable level of excitement about the enthusiasm that the “Founders” had for classical and enlightenment moral philosophy. The crux of his argument seemed to be that if everyone read more moral philosophy (or perhaps just read more books in general), our national politics would be better.

When it came to how the Founders reconciled their enthusiasm for moral philosophy with their ownership of other human beings, however, he admitted as how “They liked the lifestyle and they didn’t want to give it up.”

Even though I began my trade union career by helping to form UE Local 896, the “Campaign to Organize Graduate Students,” at the University of Iowa, and even though my father was a professor, I can’t say that I have really thought about higher education much in the almost thirty years since I left it. Since I work for a union that new represents tens of thousands of higher education workers, I figured I should attend the panel “Understanding the Crisis in Higher Education” and brush up on the political economy and organizational dynamics of the sector.

The panelists — all of whom either teach at or study public universities — pointed out that the crisis in higher education is far from new, even if it perhaps did not touch the most elite institutions until recently. As Elizabeth Shermer of Loyola University noted, even the most historically well-supported institution of public higher education, the University of California system, always relied on private money. And decades of austerity have made the UC of the 1960s positively utopian compared to what we have now.

Shermer also noted that the “historically chaotic” funding of higher education — a mix of federal and state money, private donations, tuition income and, increasingly, real estate speculation — makes the system, as a whole, extremely vulnerable to the type of political pressure that the Trump administration is now placing on it.

All of the panelists argued for higher education as a “democratic public good,” but for the most part did not elaborate on what that would mean, as if it were self-evident. (The one notable exception was Rachel Ida Buff of the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, who lamented the “deficit of poets and punk bands” resulting from the underfunding of public higher education. But I’m not sure that’s the argument that’s going to build a majoritarian political coalition.)

The week before the OAH, I was in the Twin Cities and got a chance to catch up with Peter Rachleff, a former professor of history at Macalester College and a comrade I have known since I was in grad school.

He gave me a tour of the East Side Freedom Library in St. Paul, which he helped found in 2013. The library is located in a neighborhood that used to be a stronghold of working-class “white ethnics” (i.e., people whose families immigrated to the U.S. from Europe in the late 19th century and early 20th century) and is now home to a sizable Asian population, especially Hmong refugees. As Rachleff pointed out to me, the deindustrialization that pushed much of the working-class white population out (the neighborhood lost 15,000 unionized jobs in recent decades) coincided exactly with the neoliberal destabilization of the global south that produced so many refugees and migrants seeking safety and stability in the U.S.

One of the goals of the library is to bridge the divide between the different populations in the neighborhood. They help residents “explore the history of labor, immigration, and social justice movements” through “educational resources, storytelling, public programming, performances, and exhibits.”

It is physically located in an old Carnegie library, which used to serve as the public library for the neighborhood. Rachleff told me that many an older neighbor would wander in, saying “this is where I learned to read.” You gotta meet the people where they’re at.

Saturday night at the hotel bar, I overheard two professors talking about how they discourage students from pursuing a Ph.D. in history unless they are so passionate about the subject that they cannot imagine doing anything else with their lives. They both looked to be about my age, or perhaps a little older, which presumably means that they got their Ph.D.s around the same time I did, when the bleak employment prospects at that time were a major part of why I decided not to complete my degree.

On the way to the “Hands Off” march I met a woman who teaches at a community college in New Jersey. The college has over 3,000 students enrolled; she is the entire history department.

Look, I don’t mean to pick on historians in particular — I mean, it’s not like I’m seeing the biologists or comp lit people or physicists or Lord knows the political scientists leading the charge here. (And I will admit the subtitle of this newsletter is a bit mean,; I just can’t resist that kind of wordplay.)

But someone has got to step up and articulate what “higher education as a democratic public good” might actually mean to people who have never gotten, or will never get, a college education. In one sense, historians might not be the best people to do that — historically, the U.S. has never really had a system of higher education designed as a democratic public good. The G.I. bill and the land grant program and the expansion of state-level public higher education in the 1950s and 60s were all gestures in that direction, but they were all carve-outs, partialist solutions to a universal need.

But historians are also good at, in the words of the great English historian E.P. Thompson, “rescuing” older visions and lost (or partially-lost) causes from “the enormous condescension of history.” And if we are going to have a compelling vision of higher education as a democratic public good, it has got to be rooted in some kind of conviction, like Montgomery’s and Fasanella’s, that the purpose of education is not just to improving college students’ place in the labor market, but for developing everyone, including and perhaps especially working people, into rich, knowledgeable human beings, citizens and protagonists who can take a full part in historical processes, who can be not just the subjects but the agents of history.

For those who are interested, I’ve posted the written version of my remarks at the OAH panel on the UE website. (Due to time constraints, I shortened them significantly at the actual presentation, and due to my personality, I also elaborated on certain points with anecdotes and weak jokes which were not in the written version.)

I also wrote a bit about David Montgomery last fall in Domestic Left #82:

Domestic Left #82: The past is never dead

Last summer, I got a review copy of A David Montgomery Reader, a new collection of writings by one of the greats of labor history, who passed away in 2011. Originally, I intended to review it for the autumn issue of the UE NEWS, but life happened, so I’m only halfway through the book and the review will now go in the Winter 2025 issue (though I hope to …

Last night’s full moon was the “pink moon,” named for the color of mountain phlox, which blooms in the early spring. Pink Moon is also the title of the third and final album by the 60s-era English folk singer Nick Drake, a sometimes harrowing but always beautiful exploration of existence and loss, recorded shortly before his death by suicide at age 26.

In the spring of 1995, my friend M (the one who helped me consult the I Ching a year later) came up to visit me in Iowa and I put together a few musicians to play a one-off reunion concert of sorts. (M and I had performed as a two-person band named “Liggett” — after our favorite high school librarian — at several venues in Lawrence, Kansas in the summer of 1993.)

One of the songs we performed, along with a violist and a percussionist, was Drake’s “Road,” one of the shortest songs on Pink Moon. Based on my cursory study of South Indian classical music, I decided to turn the guitar and vocal melody of “Road” into a sort of makeshift rag, the collection of notes and melodic rules that lies somewhere between a scale and a melody and forms the basis of that venerable musical tradition. (Nowadays this would probably be considered cultural appropriation — but back then we didn’t know any better.) With this approach, we stretched Nick Drake’s two-minute, four-line meditation on how different situations demand different interpretations and different actions to over more than ten minutes.

Anyway, we recorded part of the show (on a cassette tape!) and I just uploaded a digitized version of our performance of “Road” to SoundCloud. Have a listen here:

Montgomery, who essentially invented modern American labor history in the 60s and 70s, had been a rank-and-file member of my union, UE in the 1950s. A skilled machinist, he only went to graduate school after being blacklisted and unable to get a job in the industry.

I mean, perhaps their comments on why many Trump voters in states like Kentucky and Oklahoma are attached to their local public schools were, in fact, revelatory to, say, academics who have spent their whole life in elite institutions on the coasts. But to anyone who has actually been to the South or Midwest or spent much time with working-class people, I suspect not so much.