Last summer, I got a review copy of A David Montgomery Reader, a new collection of writings by one of the greats of labor history, who passed away in 2011. Originally, I intended to review it for the autumn issue of the UE NEWS, but life happened, so I’m only halfway through the book and the review will now go in the Winter 2025 issue (though I hope to get it written and posted online before the end of the year).

The essays and papers collected in the book are arranged thematically, not chronologically, but there is nonetheless a certain amount of correspondence. Three papers at the beginning of the book, one previously unpublished, were written early in Montgomery’s academic career and concern the oldest historical milieu he studied — pre-industrial American cities between 1780 and the 1840s, and particularly the city of Kensington in Pennsylvania, which was consolidated into Philadelphia in 1854, and which was home to a textile industry that predominantly employed Catholic Irish immigrants.

The historical question these essays explore, as Montgomery puts it in “The Shuttle and the Cross: Weavers and Artisans in the Kensington Riots of 1844,” originally published in the Journal of Social History in the summer of 1972, is how:

American workers in the nineteenth century engaged in economic conflicts with their employers as fierce as any known to the industrial world, yet in their political behavior they consistently failed to exhibit a class-consciousness.

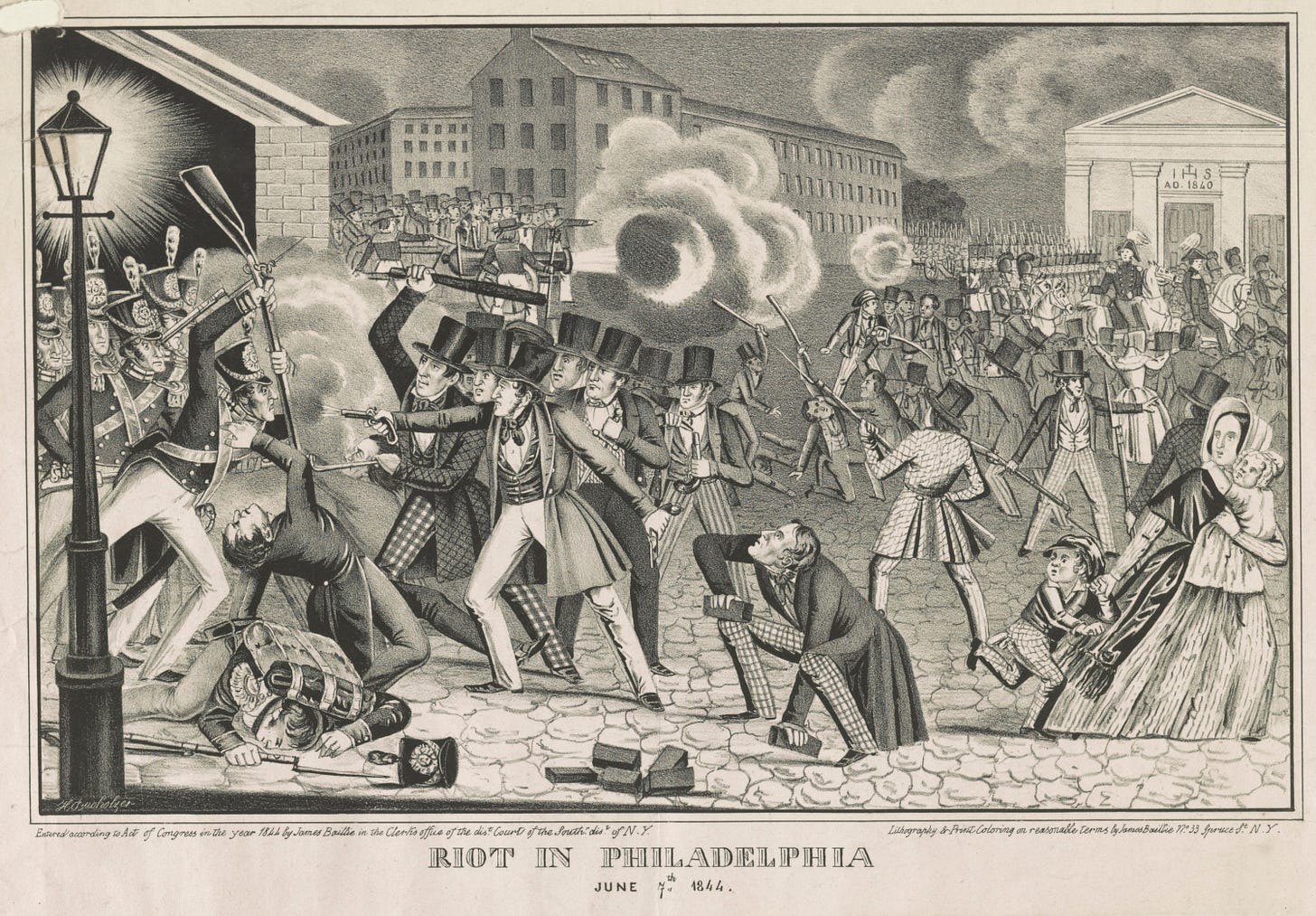

The most spectacular displays of this lack of class consciousness were two riots that took place in Kensington and Philadelphia in May and July of 1844, when nativists burned Catholic churches and homes, especially in Kensington. Most of the Irish immigrants whose homes were burned worked as weavers; the nativists counted among their ranks skilled artisans such as carpenters, blacksmiths, and tailors.

What makes this story especially heartbreaking is that less than ten years prior, the workers of Philadelphia, “Protestant and Catholic, native and immigrant, superior craftsmen, outworkers, factory operatives and laborers,” had successfully united in a general strike for the ten-hour day, what Montgomery calls “an awakening of class solidarity as significant as any in American history.” This solidarity was institutionalized in a General Trades’ Union, which also supported “successful strikes ... conducted by workers who ranged in status from laborers and factory operatives at one end of the scale to bookbinders and jewelers at the other.”

But the Trades’ Union fell apart by the early 1840s, and with its demise, “Philadelphia lacked any institution uniting the Catholic weaver, the Methodist shoemaker and the Presbyterian ship carpenter as members of a common working class.”

The 1844 riots were sparked by a conflict over whether the Protestant or Catholic bible was to be taught in the schools — they are also known as the “Philadelphia Bible Riots.” If you substitute “cultural Marxism” or “the trans agenda” for “Catholicism” (or “Romanism,” as the faith was pejoratively called by Protestants at the time), the conflict seems eerily familiar.

When we use the phrase “learn from history,” we usually mean drawing lessons from what happened in the past. Like, for example, young activists reading William Z. Foster’s American Trade Unionism, published in 1947, and using its lessons to launch an unprecedented wave of union organizing at Starbucks in the 2020s.

But there are also valuable lessons to be learned from the academic discipline of history itself, from its methodology. History is both celebrated and derided, depending on the point of view of the commentator, for being the least theoretical of the social sciences. It can sometimes seem to belong more to the humanities, and it shares with literature and philosophy an ancient pedigree that sociology and political science can only dream of. Historians tell stories, and in fact the word “story” is derived from “history,” not the other way around.

Nonetheless, at the root of the practice of history is a seemingly obvious but deeply theoretical claim: that things change over time. There are no eternal forms, and what we think of as objective categories like gender and race, or as unchanging institutions like marriage and family, are in fact historical processes that are always changing, responding usually slowly, but in some cases remarkably quickly, to the pressures and dynamics of other processes at work in society.

Montgomery worked for several years early in his career with the English historian E.P. Thompson, who coined the term “history from below.” It is no exaggeration to say that Thompson truly changed history — at least in the sense of how the discipline of history is practiced.

In the preface to his 1963 book The Making of the English Working Class, Thompson argues that class is not a “structure,” nor a “category,” but “an historical phenomenon.” He is arguing both against a certain crude Marxist conception of class as reducible to one’s structural relationship to the means of production — e.g., whether one has to sell one’s labor power in order to survive, whether works in or owns the factory — and against a static sociological conception of class as a category measurable by income, status, or education.

Instead, Thompson writes:

class happens [emphasis mine] when some men, as a result of common experiences (inherited or shared), feel and articulate the identity of their interests as between themselves, and as against other men whose interests are different from (and usually opposed to) theirs.

What Thompson describes in the over 800 pages of the book — which I devoured one summer in my late teens, eagerly turning the dog-eared and marked-up pages of my mother’s graduate-school copy of the first U.S. paperback edition — is how the carpenters, blacksmiths, tailors and weavers of England, in the years between 1780 and 1832, came to see themselves as a single “working class,” to make the English working class through their own agency.

This process is what historians have come to refer to as “working-class formation,” and it lies at the center of not only Montgomery’s work but also the best and most ambitious labor histories written since. Gabriel Winant’s much-lauded 2021 book The Next Shift, for example (which I wrote a bit about last year), is in part an examination of how the working class that was “made” by steelworkers and their families in the steel mills and neighborhoods of Pittsburgh in the middle of the 20th century was “unmade” by deindustrialization, and how the growth of the healthcare industry in its place has created the conditions for the “making” of a new working class.

For five semesters in the mid-to-late 90s I was enrolled as a graduate student at the University of Iowa, intending to study labor history. I came to Iowa to study with Shelton Stromquist1, who studied with David Montgomery at the University of Pittsburgh in the 1970s. Pitt in the 70s was where, it is not an exaggeration to say, the modern study of U.S. labor history was born. Those of us who were studying with Shel, or with other historians at other institutions who had also studied with Montgomery at Pitt, would half-jokingly refer to ourselves as “Montgomery grandkids.”

I met Montgomery at a conference at Iowa in 2011 celebrating Shel’s career, but I don’t remember having any significant interactions with him. I was no doubt too shy and, let’s be honest, star-struck — especially as someone who had dropped out of grad school — to initiate any meaningful conversation.

What I do remember from that conference is another historian, David Roediger, raising the question of “mood” at a panel he was on — specifically, questioning whether the heroic mood that much labor history tends to be written in, whether triumphalist-heroic or tragic-heroic, actually serves the labor movement and the working class. I thought it was an astute question then, and one I have reflected on even more since 2016.

The working class can make itself; it can also be unmade. And parts of the class can remake themselves — or allow themselves to be remade by other forces — in ways that include more or less of the class of people who have to sell their labor power in order to survive.

Indeed, in U.S. politics, the term “working class” has taken a strange turn in recent years, coming to signify for many not their relationship to the means of production, but their political orientation. A May survey by the Pew Research Center found not only that “Republicans are more likely than Democrats to describe themselves” as working class, but that upper income Republican are more likely to describe themselves that way (59 percent) than any grouping of Democrats. Men who “feel and articulate the identity of their interests as between themselves, and as against others” indeed.

During this past election cycle in Vermont, the victorious Republican candidate for Lieutenant Governor, John Rodgers, whose campaign funding came from the wealthiest people in the state, had lawn signs which carried the slogan “Voice of the Working Class.” In the state’s largest city, Burlington, in its most working-class neighborhood, the Old North End, the Rodgers signs were found exclusively in front of the houses owned by the worst slumlords, almost certainly placed there by their owners, not their tenants.

The title of this post comes from William Faulkner. It’s his most well-known quote, from his novel Requiem for a Nun: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Like many people, I am using it out of context. I have not read Requiem for a Nun, and a quick perusal of the plot summary on Wikipedia does not make me especially keen to do so. To be honest, I have only read one or two of Faulkner’s novels, when I was a teenager, and they were no doubt well above my head at the time.

Still, the mood that Faulkner invokes in his writing has stuck with me, even now. A suffocating mood of inheritance, whose roots we trip over as we try to run away from it, only to find its tendrils growing out of our own hearts. A mood of creeping, crippling, humid doom, thick with blood both metaphorical and physical. A mood of original sin.

Montgomery’s writing does not give us a heroic mood, but it is a much lighter, open, airier mood than Faulkner. We can certainly look around us and see the tragically divided working class of Kensington in 1844, violently at each other’s throats, living here, in our present. But the past also lives with us in the memory, if we hold on to it, of the Philadelphia General Trades’ Union, or of Kansas’s Populist governor, Lorenzo Lewelling, who during the recession of the 1890s “declared his state’s tramp act unconstitutional, and [...] ordered the police not to molest people without homes or jobs.” In a letter distributed to the state’s populace, Lewelling stated that:

The right to go freely from place to place in search of employment, or even in obedience to mere whim, is part of that personal liberty guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States to every human being [emphasis mine] on American soil.

Famously, we do not make our history under circumstances of our own choosing, but “under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.” What the study of history gives us, though, is an appreciation for the complexity of that past, and the ability to find and encounter other circumstances than the ones given and transmitted to us, other histories that we can use to make other futures.

Last Sunday night, I went to see the singer-songwriter Richard Shindell, whose music I have referenced before in this newsletter, at the soon-to-be-shuttered Club Cafe on Pittsburgh’s South Side.

Near the end of the show, as he announced that he was about to play a song by the Scottish singer-songwriter Karine Polwart, the guy next to me at the bar got very excited, naming the song he was about to play (“The Sun’s Comin’ Over the Hill”) to his partner and saying something about a Facebook post.

After he finished playing the song, Shindell remarked upon how one of the things that he loves about the song is that “all the vowels and consonants” were in exactly the right place, though he did also allow as how the song “means a lot” to him.

When I got home from the show, I looked it up. Polwart’s original recording, and a cover by the American singer Sara Milonovich on her 2021 album Northeast, are both in waltz time, but I did find a YouTube recording of Polwart singing it in straight time, as Shindell did.

I also found the Facebook post of Shindell’s that my fellow patron was referencing. It’s from 2022, and tells a quite personal story about why the song means a lot to him, and why he couldn’t really hear it the first time he heard it (and, in fact, sang backup on Milonovich’s cover version):

“I didn’t want to hear anything about any sun coming over any hill. The song is about hope and the last thing I wanted was to be interrupted by hope.”

One of the editors of A David Montgomery Reader.

A pleasant surprise to find a reference and link to Karine Polwart,whom I've followed for a while. She and I both appear in a BBC Northern Ireland TV documentary series, albeit quite separately and in different episodes.

When I was a carpenter I worked side by side with Ivy League graduates and it always struck me that the term working class was as malleable as many of the materials we built with. Whites can travel up and down the class ladder and define it for ourselves but there may never come a day when we see that privilege afforded to brown and black skinned people (and certain religions by extension). Thus the failure of this experiment called melting pot.