I couldn’t tell you when I first became aware of the paintings of Ralph Fasanella. It was probably during the mid-90s, when, in my two and a half years of graduate school, I became immersed in the worlds of labor history and labor organizing. But it is certainly possible that I could have encountered reproductions of his work in the history departments of the colleges that I attended as an undergraduate, or in the pages of history textbooks — especially the labor-oriented Who Built America?.

Regardless, Fasanella’s “images of optimism,” as his son Marc called them in his book about his father of that title, sufficiently pervaded my world that when an obituary appeared in the January 1998 issue of the UE NEWS I recognized immediately who he was, and felt proud to learn that this famous (to me) painter had once worked for the union I had been a member of for a little over two years.

The paintings were so pervasive in part because they lent themselves exceptionally well, in both subject matter and style, to being reproduced as posters — and in my memory, at least, those posters adorned the union halls and offices where I cut my teeth as a trade unionist, and were offered for sale at the North American Labor History Conferences I attended in Detroit and the “Meeting the Challenge” labor conferences I attended in the Twin Cities during those formative years. (One can still purchase reproductions of his work from museums.co.)

In the admittedly small world of left-leaning trade unionism, Fasanella’s art had achieved a certain ubiquity, one that became even greater as the internet allowed for the ever more frictionless reproduction of images. (Nowadays, if I am talking to someone about Fasanella and they are not familiar with his name, I can simply pull up one of his Lawrence strike paintings on my phone — which will often lead to a quick assent of recognition.)

His work, thus, arguably embodies exactly the kind of “revolutionary demands in the politics of art” that Walter Benjamin writes about in his famous 1935 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”:

One might generalize by saying: the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition. By making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence. And in permitting the reproduction to meet the beholder or listener in his own particular situation, it reactivates the object reproduced. These two processes lead to a tremendous shattering of tradition which is the obverse of the contemporary crisis and renewal of mankind. Both processes are intimately connected with the contemporary mass movements.

Nonetheless, when Marc Fasanella, whom I interviewed for a 2022 UE NEWS feature I wrote about his father, let me know that an exhibit of Fasanella’s paintings was going to open in the Catskills in January, I jumped at the chance to see his work in person.1 To see what Benjamin called the “aura” of a work of art, “that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction.”

The show, titled Seen: Six Decades of Ralph Fasanella Paintings, is at the Ruffed Grouse Gallery in Narrowsburg, New York — a charming hamlet of fewer than 400 people which sits perched over the Delaware River narrows, right across from Pennsylvania’s eastern border. Narrowsburg’s downtown is only about two blocks long, but features two coffeeshops, a bookstore, a brewery, and a classy yet unpretentious French restaurant. The gallery lies about a block south, past the Narrowsburg Feed & Grain Company, where dozens of crows congregated on the feed mill towers, and under a set of railroad tracks.

The exhibit contains both some of Fasanella’s earliest paintings, from 1947, and some of his last — Baseball, Holy Cow! was completed in 1996, less than two years before his death. It includes two paintings from his well-known Organizing Committee series (set in union halls they ... are a favorite poster for union halls) but also portraits, scenes of leisure as restaurants and beaches, and what can only be described as fantasias. As I wrote in my review for the UE NEWS:

Fasanella was interested in every aspect of working class life, not just union struggles. Here we see working people at home and at the beach, vacationing, eating hot dogs at the iconic Nathan’s in Brooklyn, and enjoying America’s favorite pastime. ...

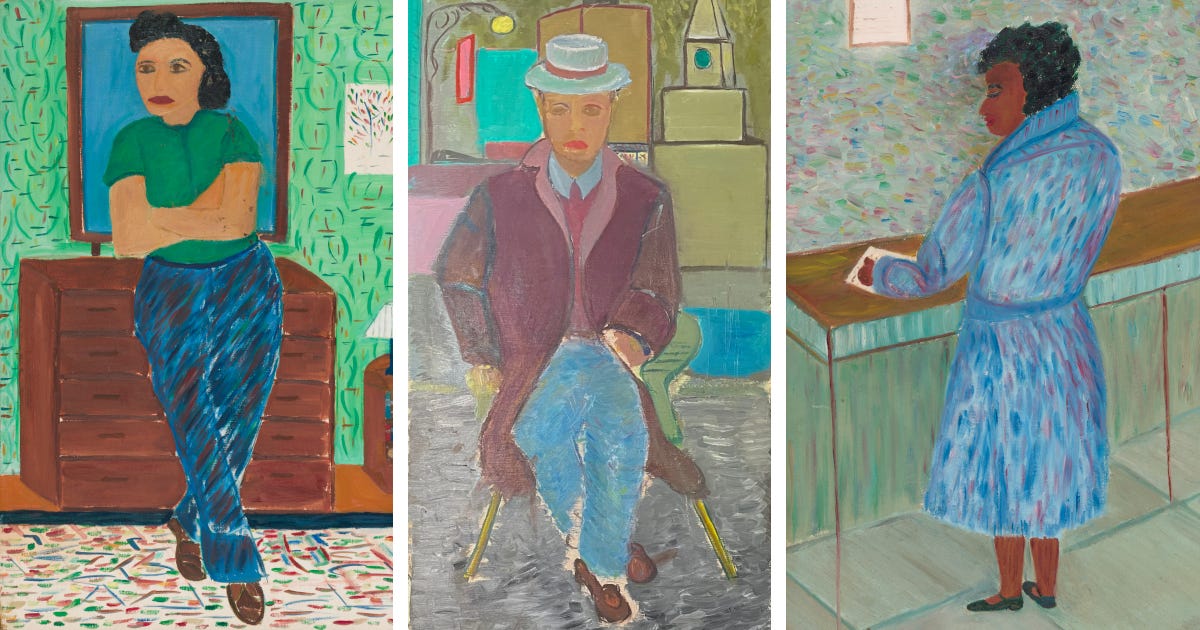

Many of the paintings in the show are studies of single individuals: a woman in a green sweater leaning against a chest of drawers from 1955, a man in a maroon coat seated in front of a city scene from 1960, a Black woman in a blue coat applying for jobs at a U.S. Employment Services office from 1955. ...

Seeing Fasanella’s sensitive characterization of his subjects in these portraits gives one a new appreciation of the care he took in painting each of the dozens (or even hundreds) of people in his larger-scale paintings. ... One could say that Fasanella paints his subjects the way an organizer might, aware of the potential of the collectivity but always attentive to the personalities and interests of each individual worker.

One of the things that most struck me about seeing the paintings in person was the frequency with which Fasanella used repeating grids in the composition of his paintings. His city scenes, of course, are full of the kind of six- and seven-story apartment buildings common in mid-century New York City, where Fasanella was born and lived his whole life, with their rows of repeating windows (often filled with human figures in his paintings). And his paintings of mill buildings and dress and machine shops also feature repeating windows, each one often made up of grids of smaller panes of glass.

But it is most striking in his interiors, where the grids lie at a slant angle. The floors and roofs of the union halls in the Organizing Committee series are tiled, often in a checkerboard pattern, as are the floor and the blue wall behind the service counter at Nathan’s. Even the grass on the baseball field is rendered in part as a checkerboard of two different shades of green.

In this, they are somewhat reminiscent of paintings from the Renaissance, when the rules of mathematical perspective were “discovered,” allowing painters to create a sense of three-dimensionality in their two-dimensional medium. And indeed Fasanella’s work has a depth and sense of space that is often lacking in the work of other self-taught artists. But he does not adhere to the strict mathematical precision of “proper” perspective — the straight lines of his grids aren’t even always straight — which allows his geometries some wiggle room.

This wiggle room is used to capture a particular kind of space — the urban space of a crowded city like New York, where Euclidean theory must yield to the practical reality of getting so many people into such a small container.

In 1972, when Fasanella was “discovered” by the art world, he was called a “primitive” painter (a label he rejected) and often compared to Grandma Moses, a farm wife from upstate New York who, like Fasanella, was self-taught as a painter.

Moses’s work, which gained popularity in the 1950s, consisted of what Moses herself referred to as “old-timey” scenes of rural life in New England.2 It is not hard to imagine why her nostalgic paintings of rural American life, invocations of a time before industrialization and immigration transformed American life, were widely embraced in 1950s Cold War America.

Yet Moses’s painting technique, curiously enough, in fact often drew from precisely the kind of mechanical reproduction that Benjamin heralded as essential for democratic, even revolutionary art. To compose her paintings, she would often cut out figures from pictures in mass-circulation magazines like Time and LIFE — the very publications which made her famous by reproducing her paintings for a mass audience — and arrange them on her canvases, then paint over them.

Fasanella drew from a different well of modernism, which the Ruffed Grouse exhibit makes clear. Ryan D. Ward, the owner and director of the Ruffed Grouse Gallery, pointed out to me how early paintings like Nocturne (1947) indicate how Fasanella taught himself to paint by “going to museums and looking at Picasso and Matisse.” Nocturne depicts Matisse-like red and black figures in and around a building rendered in a particularly trippy, almost Cubist perspective. The side of the building features an early version of Fasanella’s gridded style; if we take the repeated squares as windows (though they could also be posters or flags), it would indicate that the building rises to six stories.

The front of the building, though, displays a single interior in cutaway, occupied by a single red figure, towering over her compatriots on the street outside. (There is a certain suggestion that the figures are all sex workers.) Vaguely hieroglyphic patterns rise along the front of the building on either side of the cutaway, and in the lower right-hand corner a semi truck, rendered in reds and dull greens, is turned at an impossible angle, reminiscent of the figure in Marc Chagall’s Birthday.

Fasanella was born in the Bronx, the son of working-class Italian immigrants. His mother was a devout anti-fascist and, in his 20s, Ralph joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigade to fight the fascists in Spain. Returning to New York City, he got a job at the Morey Machine Shop in Brooklyn and became a member of UE Local 1227; in 1940 he joined the UE staff as an organizer. He initially took up painting as a way to soothe the arthritis in his hands; by the early 1950s he had left the union staff, either to pursue his passion for painting or because of layoffs necessitated by the union’s postwar membership losses (accounts differ).

Blacklisted due to his political commitments, he was unable to either find employment in the machine tool industry or show his work in most galleries. He supported himself and his family by operating a gas station in the Bronx until the early 70s, when he finally became able to support himself by selling his paintings.

He was, above all, a painter of New York City, formed by an era in which, as historian Joshua B. Freeman writes in his book Working-Class New York, “the New York labor movement led the city toward a social democratic polity unique in the country,” one “committed to ... popular access to culture and education.” (A book of Fasanella’s paintings published in the early 70s was appropriately titled Fasanella’s City.)

When Fasanella was organizing workers into amalgamated3 UE Local 475, it was the largest local in the third-largest CIO union in the country. The CIO, especially in New York City, was more than just a federation of unions; it was, in its heyday, a vibrant social movement, one committed — at least on its left wing — to internationalism, anti-racism, and broad social equality.

Spending time with Fasanella’s paintings in person, you can not just see but feel his ongoing commitment to that vision, his belief in the potential and value of every single member of the working class, whom he painted with such care. This is not the so-called “working class” invoked as an avatar of virtue by Trump or J.D. Vance (or, conversely, as an avatar of violent ignorance by elite liberals), constituted by manly work, white purity, and conservative social mores. This is the actual class of people who depend on work for a living, the people without whose brain and muscle not a single wheel can turn, the people in whose hands is placed the power to bring forth a new world from the ashes of the old.

The centerpiece of the show is undoubtedly Love Goddess, a fantastical tableaux which measures almost four feet high and almost seven feet wide, a monumental scale that begs to be seen in a major museum. Painted in 1964, it is remarkably predictive of the cultural and sexual revolutions that would scandalize the country later in the decade (though perhaps New York City was, as it usually is, just ahead of its time).

The right half of the painting is dominated by a large, romanesque church, painted in vibrant reds and blues, with colorful, abstract stained glass windows. The church, however, is devoid of people.

Instead, the people in the painting congregate on a lawn to the left. There, they sit at tables, lie on the grass, converse, embrace, and kiss, in groups and in pairs. One young woman plays a guitar; another lies naked on a table. A priest and a monk mingle with the crowd, seemingly unfazed.

And in the middle of the revelry, a massive outdoor altar to sexual and romantic love, featuring both traditional symbols of Christian worship like crosses and chalices and more pagan and earthly images: a large female figure, posed like Botticelli’s Venus but dressed like a pinup girl, and a bed, perhaps inviting some kind of ritual, public display of more than affection.

Like all great art, Love Goddess defies simplistic explanation, while opening itself up to a multitude of interpretations. While Fasanella’s paintings, especially the ones displayed as posters in union halls, can seem nostalgic to us now (especially as those of us in the labor movement look back to the glory days of the CIO), this painting scrambles everything we thought we knew about Fasanella, and reminds us that, even when he was painting images from the past, he was looking to the future, and for liberation.

In 1972 Fasanella travelled to the mill town of Lawrence, Massachusetts, a trip that resulted in a series of 15 paintings about the then-largely forgotten “Bread and Roses” strike of 1912, perhaps his most well-known work.

There is one painting of Lawrence in the Ruffed Grouse show. Titled simply Paper Mill, Lawrence, it was painted in 1976, several years after the strike paintings. Eerily, and uncharacteristically for Fasanella, it contains no people, just a scene with a nineteenth-century brick mill on the left-hand side of the painting, a dark red sky with a full moon (or perhaps the sun, obscured by smog), the river, which takes up most of the bottom half of the painting, and an empty bridge bisecting the composition horizontally. There are no workers; the mill could well be empty and unused, as much a part of the quaint New England past as a Granda Moses painting.

In 1976, of course, Fasanella could not have known the degree to which Lawrence would be decimated by deindustrialization in the coming decades. The painting is most likely of the Merrimac Paper Company, which opened in 1866 and kept operating for almost three decades after Fasanella painted it. Nonetheless, he may have sensed that something bad was on the horizon.

The confident “working-class New York” that Freeman describes (and celebrates) in his book was, by the middle of the 1970s, already being consigned to the past. The 70s were famously the decade of New York City’s great fiscal crisis, when finance capital decided to pull the plug on the city’s generous welfare state and pioneered what came to be known as “austerity.” But the groundwork had been laid earlier, as the city, once a major manufacturing center, deindustrialized in the 1950s.

In 1954, UE Local 475 members at the American Safety Razor plant in Brooklyn staged one of the few sit-down strikes of the postwar era in an unsuccessful bid to keep their plant from closing. While the enticement of being able to pay lower wages by relocating to Virginia was undoubtedly a pull factor in ASR’s decision to leave, the rising rents and property taxes in New York City were an even bigger push factor.

As journalist Robert Fitch demonstrated in his 1993 book The Assassination of New York, the FIRE sector (“Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate”) made a conscious effort to push manufacturing, with its troublesome unions, out of the city in the postwar era. The success of this effort led directly, and perhaps consciously, to the fiscal crisis. As well-paying and unionized factory jobs became scarce, so-called “white ethnics” — including probably many of the 600 workers laid off by American Safety Razor — began to drift away from the generous, optimistic vision of New Deal liberalism and embrace a more resentful, reactionary politics, of the kind that helped propel Ed Koch to the mayoralty in 1977.

The fourth and final part of Freeman’s Working-Class New York describes how in the 1980s “the growth of international business and an influx of foreign money, businessmen, and tourists transformed the character of New York.” It was a decade in which “[a] culture of celebrity came to dominate public life that had little place in it for the ordinary toilers and their kin” — in which New York, in many ways, ceased to be Fasanella’s working-class city. Writing in the late 90s (the book was published in 2000), Freeman chose to title this part of his book, the tragic denouement, after the figure who most clearly embodied his city’s turn away from the working class: “Trump City.”

The Merrimac Paper Company building, abandoned since the company closed its doors in 2005, was destroyed by fire in 2014.

Seen: Six Decades of Ralph Fasanella Paintings will be on display at the Ruffed Grouse Gallery in Narrowsburg, New York through April 6. Ruffed Grouse will also be exhibiting Fasanella paintings, alongside those of other artists, at the Outsider Art Fair in New York City from February 27 to March 2.

All images courtesy The Ruffed Grouse Gallery and the Estate of Ralph Fasanella.

While it is possible that I have been in the presence of a Fasanella painting before — his painting “Subway Riders” is on display at the 5th Avenue/53rd Street subway station in New York City and one of his Lawrence strike paintings hangs at the AFL-CIO building in Washington, DC — neither of those settings encourage close observation.

Moses lived most of her life in Washington and Rensselaer Counties in New York, which are not strictly part of New England, but close — they border Vermont. The largest public collection of her work resides at the Bennington Museum, in the southwest corner of Vermont.

An amalgamated union local is one which includes workers from many different employers. The largest single-shop local in UE at the time was at the Westinghouse plant in East Pittsburgh, which at its peak during World War II employed something like 20-30,000 workers.

I gotta get to Narrowsburg by April!

Love the art.