If you visit Gertrude Abercrombie: The Whole World Is a Mystery, which is at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh through June 1, be sure to walk through the whole exhibit at least twice. The paintings, which span the three and a half decades from 1937 to 1971, are arranged in more or less chronological order, and re-viewing Abercrombie’s earlier paintings in light of her later work reveals continuities and themes that are perhaps not immediately obvious if you view them in the order intended.

The exhibition guide states that the paintings are “imbued with autobiography that revealed her emotional truth and declared it as real,” but its authors wisely refrain from providing too much biographical detail, other than the fact that Abercrombie, who was white, “surrounded herself with Black jazz musicians [and] created community with queer painters, poets, and others outside the mainstream,” and that she had a “tumultuous” love life, including two marriages and two divorces.

But you don’t need to read the guide to realize that Abercrombie’s paintings are deeply personal. Even if the lone woman in many of her paintings did not resemble her, it would be obvious that this figure, not always the only figure but always standing alone, and always in a dreamlike setting, represents the artist’s consciousness.

Although I’m pretty confident I have never seen an Abercrombie painting before, they feel remarkably familiar. Partly this is because the surrealist idiom in which she worked “has been whisked into the batter of our world until it flavors everything,” as New Yorker art critic Jackson Arn puts it in “The Bad Dream of Surrealism.”

Surrealism, which talked so tough about realism’s silly conventions, ended up with enough of its own that they may as well have been — how should I put this? — taken from some stock catalogue.

There they are, the disparate objects assembled on a flat plain, with little sense of motion, as if to make it clear to the viewer that they are symbols — though of what, the viewer, and perhaps even the artist, might have little idea. In Abercrombie’s case, the plain is generally more verdant than the deserts favored by European surrealists — her landscapes were apparently mostly inspired by the small city of Aledo, Illinois, where she spent a formative portion of her childhood — and many of her tableaux are set in urban interiors rather than landscapes. There are even traces, in a few of the paintings, of the surrealists’ fondness for binding and dismembering women’s bodies, though that reads very differently coming from Abercrombie, who is presumably recording some kind of emotional1 violence done to her, rather than the domination fantasies of, say, a Man Ray.

But there are other, more American, familiarities at work here as well. The second room of the exhibit is titled “Bop Art,” and none other than the legendary bebop trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, a close friend of Abercrombie’s, proclaimed that she “is the bop artist, bop in the sense that she has taken the essence of our music and transported it into another art form.” The repetition of certain iconic objects (owls, white towers, the moon) across her paintings, and the repetition of objects (trees, pillows, doors) within individual paintings — often painted identically except for their color — are reminiscent of the way bebop musicians solo over multiple “choruses” of the same Tin Pan Alley tune, turning the chord progression inside and out and finding new resonances in it each time.

The biggest resonance for me, though, is with the regionalist American painters that were Abercrombie’s contemporaries — painters like Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, and especially Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Wyeth. For these painters, the American landscape was already suffused with plenty of emotional and psychological meaning — Wyeth’s Soaring (1950) is, for my money, far more unsettling than anything the European surrealists ever came up with, even though its depiction of three vultures circling above a Pennsylvania farmhouse is perfectly “realistic.”

Reverie (1947), in particular, is eerily reminiscent of Wyeth’s famous Christina’s World (though the latter wasn’t painted until a year later). A woman, her head turned away from us, reclines in the foreground, gazing between two small hills at a body of water illuminated by a full moon. The stand of stylized, leafless trees on one hill, the featureless dark-red cube atop the other, and the shockingly white handkerchief or piece of paper on the ground beside the woman all place the painting firmly in the surrealist genre, but in its depiction of a lone figure confronting a landscape that is neither entirely natural nor entirely man-made, familiar but not without menace, it is as thoroughly American as any regionalist.

Both of the times I have visited the exhibit since it opened on the 18th I have been put in mind of the Hermetic saying “as above, so below,” which reflects occultists’ belief in a rule of correspondence between the heavenly and earthly realms. Although there is no indication that Abercrombie was particularly interested in Hermeticism or any other form of occultism, there is a recurring visual theme in many of her paintings of connection between the earth and the heavens. Between Two Camps (1948) is bisected by a string running from the upper left to the lower right, connecting a flying kite to a stake in the earth. More explicitly dreamlike are Two Ladders (1947), in which the eponymous ladders ascend to a crescent moon and a cloud respectively, and Moored to the Moon (1963), in which another crescent moon is tied by a rope, which also bisects the composition diagonally, to a lone mooring post in the middle of an expanse of water.

Abercrombie’s paintings are full of other objects that signal the presence of sorcery or enchantment — owls, cats, flag-topped tents, wands — and a few paintings, such as Levitation (1967) and The Magician (1964), which literally a magician. Her still lifes, collected in a section of the show called “An Unstill Life,” depict, not flowers or fruits, but objects such as shells and leaves, dice and dominoes, and switches of hair — all objects one could easily imagine being used in occult rituals. In some cases she painted these still lifes in boxes, into which she would place the actual objects she was rendering, and she often executed her still lifes as tiny miniature paintings that could be worn or carried — talismans, perhaps, to allow the wearer to carry a piece of the dream world into waking life.

Her work is also full of the kind of eerie twinnings that often characterize magical practice, especially in Strange Shadows (Shadow and Substance), from 1950. A woman stands on the left, her hand outstretched but empty, casting a shadow which renders, not as the shadow of a woman but of a tree, with an owl perched in the branch that echoes her outstretched arm. On the right, a goblet sits on a pedestal, but the pedestal casts the shadow of a woman facing left and holding out the goblet as if offering it to the woman/tree on the left. A clock and an owl rest on the floor, each one forming a triplet with one of the figure/shadow pairs — another musical motif. A sign on the wall proclaims, simply, “LATER.” It is the most unsettling painting in the show.2

The next-to-last section brings together a series of paintings called Demolition Doors, each of which depicts a row of brightly-colored doors. They are perhaps the most formally “bop” of her paintings, with the doors varying not only by color but also by height, width, and design. As the guide explains:

This subject did not solely spring from Abercrombie's imagination. For these works, she found the fantastic in the real, basing her paintings on what she observed in her neighborhood: doors were being removed from buildings prior to demolition and assembled as walls around construction sites. In the 1950s, Hyde Park underwent one of the nation's largest urban renewal plans, spearheaded by the University of Chicago. Assisted by new federal, state, and local legislation designed to eliminate perceived urban "blight," the university sought to create a neighborhood that would be white and affluent, effectively displacing a Black population that grew as a result of the Great Migration.

In her earlier work, Abercrombie had made her paintings “surreal” by taking an everyday object such as a chaise longue or a marble-topped table — or a door — out of its domestic setting and placing it alone, out of context, in an imagined dreamscape. Now, in her neighborhood (Abercrombie lived in Hyde Park from the 1930s until her death in 1977), the forces of “realism” were literally tearing the doors out of people’s homes and assembling them, out of context, into a nightmare of displacement and raw power.

The show guide doesn’t talk about Abercrombie’s politics, beyond stating that she “had no tolerance for prejudice,” but it seems reasonable to assume, given her multiracial, bohemian social life and the fact that she was employed from 1935-40 by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project,3 that she was broadly aligned with the New Deal, and particularly with that wing of the New Deal coalition that fought for racial equality. By the mid-50s, when she began the Demolition Doors series, that wing — which included my union, UE — had come under ferocious attack for being “communist-dominated” (though really for, you know, challenging white supremacy and capitalism).

I am not trying to ham-fistedly force politics into Abercrombie’s work, which was for the most part intensely personal and therefore pre-political if not necessarily apolitical.4 But these paintings did make me think a lot about George Lipsitz’s collection of essays Rainbow at Midnight: Labor and Culture in the 1940s. In several of those essays, Lipsitz argues that, with the advent of cold-war repression, the liberatory and utopian impulse that the working class expressed through trade unionism and New Deal politics from the 1930s through the immediate postwar era was channeled underground into vibrant new cultural forms: rock and roll and roller derby, among others.

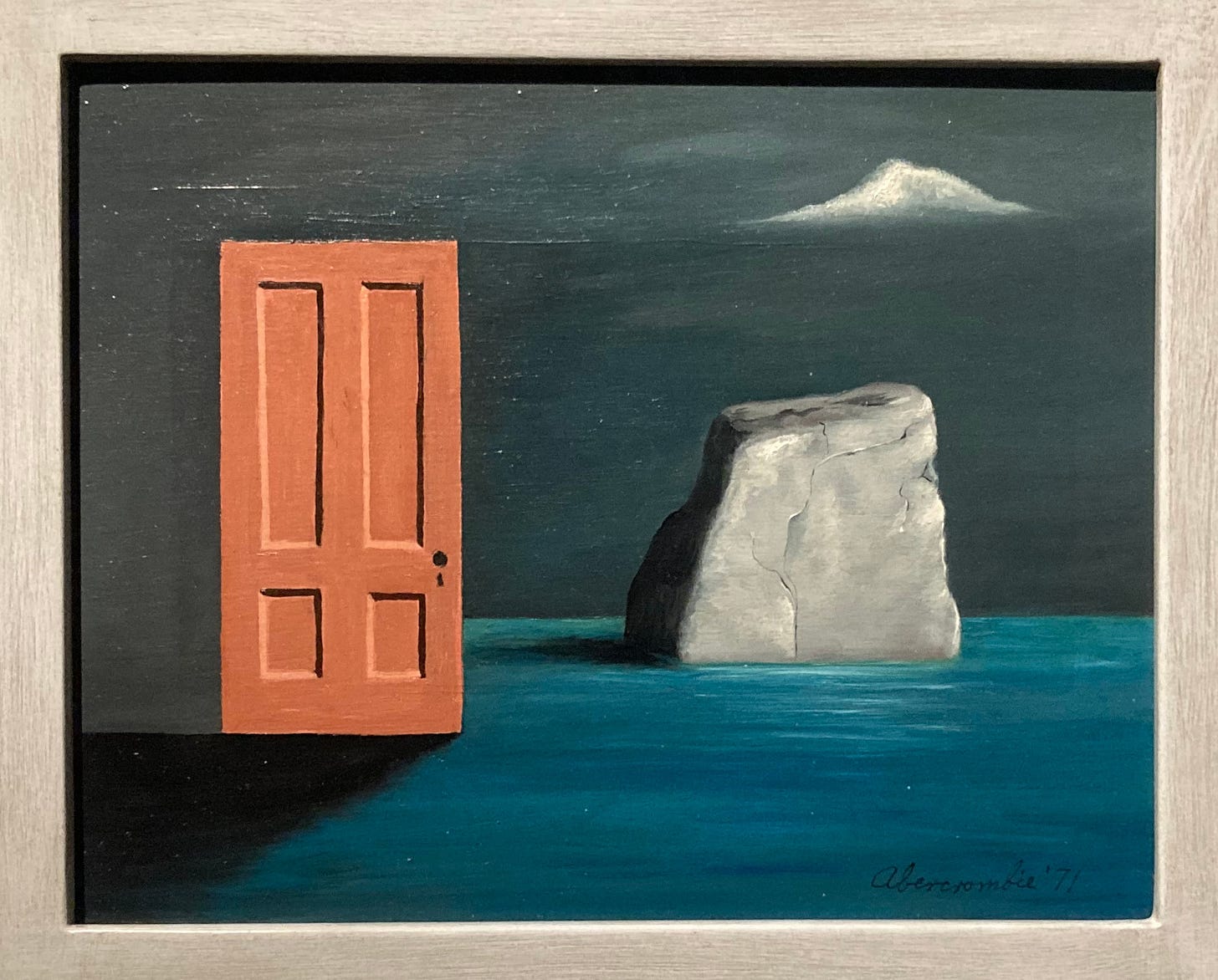

Abercrombie, whose health began declining precipitously in 1959 and who suffered from depression, did not produce vibrant art as the Cold War settled in. Instead, the Doors paintings strike a note of sad resignation; they are almost Edward Hopper-like in their depiction of the empty urban spaces in which the doors stand guard, with no figures beyond an occasional black cat. Her late paintings are similarly melancholic, such as The Door and the Rock (1971), one of her last, which depicts a drab interior with an orange door melding into a seascape with a boulder, and a snow-covered mountaintop far in the distance.

Still, the melancholy of her late work highlights the restless urgency of the earlier paintings, and how they must have in some way reflected a certain utopianism among her cohort in the New Deal era. Certainly her construction of a bohemian community of people “outside the mainstream” indicated a interest in creating new forms of social life.

Abercrombie’s life was clearly never simple, emotionally or otherwise, and her paintings reflect that. But if the whole world is a mystery, as she claimed, then it is also a world of radical possibility, certainly in art and also, perhaps, in life.

Gertrude Abercrombie: The Whole World Is a Mystery is on display until June 1 at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. It will then go to the Colby Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine from July 12 through January 11, 2026, and to the Milwaukee Art Museum from March 27-July 19, 2026.

Abercrombie not only hung out with jazz musicians, she also played piano, and would regularly host jam sessions at her home. The Carnegie has put together a playlist inspired by her tastes and friendships:

Or perhaps other kinds of violence as well, though I am unaware of any indication that Abercrombie ever suffered physical abuse.

The exhibition guide tells us, though I kind of wish it hadn’t, that this painting — along with several others — is about Abercrombie feeling torn between her two husbands, the second of which she was having an affair with while still married to the first. The clock apparently represents the daughter Abercrombie (who according to the guide “displayed minimal interest in motherhood”) had with her first husband.

My favorite painting in the show, The Pump (1938), bears a metal label reading “WPA Federal Art Project” affixed to its wooden frame.

I know, I know, “the personal is political.” But I would argue that in order for the personal to actually become political, it has to concern itself with some kind of collectivity of personal experiences — such as, most famously in terms of that phrase, women’s personal experiences of patriarchal oppression. Abercombie’s paintings, while they might arguably create the conditions for such collective concern, do not, as far as I can tell, pursue it.