Domestic Left #87: Bum a smoke?

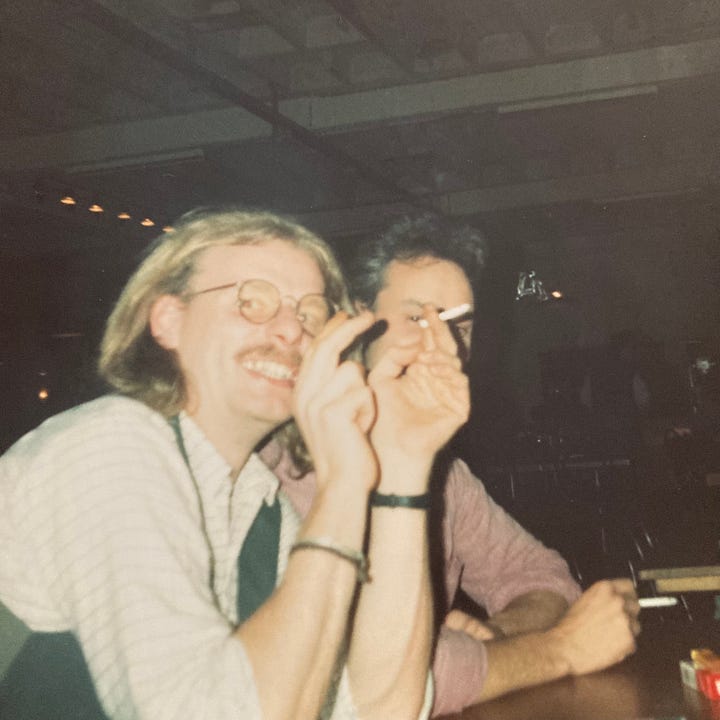

We were dancing in a second-floor nightclub downtown when my friend J, the drummer in one of the bands I was in at the time, offered me a cigarette. If I recall correctly, it was an unfiltered Camel. It was 1989, and as 80s kids we had been made fully aware of the dangers of smoking. If we were going to poison our lungs, we were going to do it to the max.

That first cigarette was my initiation into a curious society, one that at the time spanned a wider range of people across class and culture than I suspect it does now. Spread across one of the most individualistic and possessive countries in the world, we all knew that, if asked, we were honor-bound to provide a cigarette or a light — that our packs and our lighters were not solely our own, but in a sense communal. And that if we had a cigarette but no way to light it, or a craving for nicotine but no smoke, we could rely on our friends or even strangers — a thin, tawdry safety net, but a kind of safety net nonetheless.

For most of the next decade, from age 16 into my early 20s, I was a casual, on-and-off-again smoker of cigarettes. In my mid-20s, retroactively surveying my history of smoking, I would tell people that I would start smoking as soon as I started working an hourly job, and stop again as soon as I quit.1

That wasn’t strictly true (although I do remember stopping to buy a pack on my way home from my first shift at Packer Plastics after at least a year of not smoking at all), but it did capture an important part of why, having started smoking because it was cool, I continued to draw noxious tobacco fumes into my lungs on a regular basis, even as I realized how it made my clothes and my apartment and my very body stink.

As I approached the end of my senior year in high school, I opted not to go to college, but instead to pursue rock-and-roll stardom with J. He was working at the Lawrence outpost of VistaBurger, at the time a small regional fast-food chain based in Manhattan, Kansas. (The original restaurant in Manhattan remains open, but all of the others have since closed.) He helped me get a job there, and we got a place together in an unremarkable, utilitarian apartment block. Our flat was half-basement, its handful of high, small windows level with the parking lot outside, and we filled the dreary, characterless space with smoke and ash.

At Vista, I began wiping down tables, taking orders, frying onion rings and corn dogs, and flipping burgers that a button I had to wear proclaimed were made from 100% Kansas beef. I made $4 per hour, an exciting 20 cents above the minimum wage at the time, and my 30 hours a week or so covered rent, food, guitar strings, a monthly shopping trip to the thrift store, and maybe a pack a day of cigarettes, whose nicotine bitterness helped cut through the haze of grease that would cling to me on the half-hour walk home.

The advantages of being a smoker became immediately apparently to me during my first week on the job. We all got our state-mandated 15- and 30-minute breaks, depending on the lengths of our shifts, but when work slowed down after the lunch or dinner rush, smokers could always, within reason, “go have a smoke.”

After my rock and roll dreams came crashing to earth, I lived for a while in Vienna, and I took to smoking Gauloises, an unfiltered French cigarette of strong, dark tobaccos from Syria and Turkey. Smoking them in Vienna’s cafes, along with an espresso and a novel or book of philosophy, gave me a sense of a new kind of cool, one that at least partly made up for the fact that I would never be a rock and roll star.

Gauloises are arguably the coolest cigarettes in the world. They were Albert Camus’s favorite brand. In fact, in 2016 the French government considered banning them for being just. too. cool.

The not-so-secret society of smokers was even then being pushed, physically, away from the mainstream. When I worked at Vista it still had an indoor smoking section — six sad tables in the back of the dining room, past the restrooms. When I worked at Packer Plastics, we had to leave the building entirely.

Yet this casting out made us convivial. Workers who took their breaks inside did so, generally alone, at long tables in a dreary, neon-lit cafeteria with low ceilings and no natural light. We happy smokers, in contrast, laughed and traded lights and puffed and chatted away at a handful of picnic tables under the stars. (I worked third shift.)

The few times I took a train long distance, I spent most of the trips in the only place on the whole train where you could still smoke, the small smoking section of the dining car, where I would inevitably make new friends. More times than not, we would end up sharing the most intimate details about our lives, confident that what was spoken in the smoking area would stay in the smoking area — or at least not follow us back into our real lives where, pre-internet, we would have no way of tracking each other down.

A few months ago, the Guardian ran an article about how, since the UK enacted a ban on indoor smoking in 2007, the smoking areas outside of nightclubs have become “where all the best socialising happens.”

To some people, the nightclub smoking area offers a moment of relief from the ear-rattling speakers and clouds of dry ice inside. For others, it’s an opportunity to sit down and chew the fat with a friend, or to forge a connection with a new one. Rarely is it just about having a cigarette. Whatever its function, a trip to the smoking area has become a ritual part of the night for many clubbers, regardless of whether they smoke or not.

During the years I was taking up smoking, Richard Klein, a professor of French Literature at Cornell University, was trying to quit. As he was doing so, he wrote Cigarettes Are Sublime, a 232-page meditation on cigarettes and the appeal of smoking originally published in 1993.

He argued that cigarettes perfectly fit Kant’s definition of the sublime, which gives us “at once a feeling of displeasure, arising from the inadequacy of imagination in the aesthetic estimation of magnitude to attain to its estimation of reason, and a simultaneous awakened pleasure, arising from this very judgement of the inadequacy of sense of being in accord with ideas of reason.” In other words, the sublime is something we cannot control or even fully understand, and our lack of understanding and control pleases and terrifies us at the same time.

I would fact-check this section against my copy of the book, except twenty years ago I mailed it off to an ex-girlfriend I used to smoke with.

As a kid in the 80s, I was fully indoctrinated by the anti-smoking propaganda2 that filled the schools at the time, and it was effective enough while I was young that my sister and I campaigned to convince our father to stop smoking. (A campaign that was ultimately successful, though, I learned later, not as quickly as we had thought — he continued to smoke secretly for a couple of years after he told us he had quit.)

He had picked up the habit in the 60s — when tobacco companies widely promoted cigarettes as healthy, for fuck’s sake — during a year he spent in Nigeria, teaching economics in a Peace-Corps-like program. Plates of cigarettes would be offered at parties, and if you could not find anyone to talk to, you could always grab a cigarette.

In those days before smartphones, cigarettes were not just a tool for socializing, but armor for solitude. If you were smoking, you weren’t just standing or sitting there alone, you were doing something. Your hands had purpose, your senses were being stimulated. Your gaze into the distance was not the sad stare of a lonely man or woman but the sharp sizing up of a lonesome drifter, the cool look of a femme fatale, the keen observation of a philosopher.

And, of course, you were looking cool. You weren’t just alone, you were having a smoke.

The band J and I were dancing to that fateful night was called The Homestead Grays, named after (though so far as I know having no connection to) the famed Negro Leagues baseball team from Homestead, Pennsylvania. They were one of the most popular bands on the local music scene in Lawrence in the late 80s, and played what might be called today “Americana” or “alt-country” music, though a particularly light-hearted and party-oriented flavor of it.

The lead singer of that band, Chuck Mead, later moved to Nashville and found a certain amount of success on the country charts with BR5-49. In 2009, he released a solo album, Journeyman’s Wager, which I ordered on CD directly from his website. I must have put something in the comments field about smoking my first cigarette at a Homestead Grays show, because the CD came in a case signed by Mead with the inscription “Sorry about that first cig.”

Even now, whenever I am approached by someone on the street asking if I have a cigarette or a light, I feel a twinge of guilt for not being able to help them with their fix. On more than one occasion I have in fact considered buying a pack and a lighter solely to be able to provide this service to my fellow members of the society of smokers, which you never truly leave.

On more than one occasion I have also considered the possibility that it might be, on balance, healthier to pull out a pack of cigarettes and have a smoke than to pull out my smartphone and have a scroll.

Although it seems hard to imagine now, when I finally went off to college, they had dorms rooms you could smoke in, and assigned roommates in no small part based on whether you were a smoker or not. I checked the box that said I was a smoker. Because I was cool, man. Or at least thought I was.

I was assigned a roommate whose name I no longer remember, though I remember what he looked like, especially his long, straight, black hair, and that he was from Alabama. Like most new college students who have met exactly one other person on their first day, we went together to the social events designed to socialize us, but we quickly gravitated to different circles. He fell in with a group of young men who styled themselves the “Andrews House Posse,” most of whom lived in a quasi-dorm called Andrews House.3

The AHP were much cooler than my friends. They were partiers, and rumored to be into hard drugs; my social circle in college rarely even touched alcohol (I had gotten most of that out of my system during my rock-and-roll “gap year”). In that context, I stopped smoking entirely. My roommate and I not only kept different company and different habits, we kept different hours, and after those first few days almost never spoke with each other. At the end of our first semester, we arranged some complicated multi-person, multi-room swap which allowed an AHP member to move into my half of the (coveted) smoking room, while I moved downstairs into a non-smoking room.

Years later, when I came back to visit during my senior year (I had transferred to a different college, back in the Midwest, after two years), I spent some time talking with my old roommate. Being at that point super-mature 21-year-olds, drinking legally at a bar in town, we reflected on our inability to communicate when we were young. In his soft Southern accent, he told me how, when he arrived at this fancy Northern college with all these rich kids, he was just angry all the time, except when self-medicating with drugs and booze. I told him how I was terrified of his coolness, and the coolness of the cool kids he ran with, smokers all. We laughed about it.

I do not remember whether we smoked cigarettes together or not during that conversation, but it seems likely.

Thankfully, I never had any problem quitting cold turkey — at least when quitting smoking coincided with quitting a job. And when, in 1998, I got an hourly job at the Flynn Regional Box Office — a union job with very little stress — I felt no desire to pick up the habit again.

I fully support educating kids — and, for that matter, the public in general — about the dangers of smoking. But it’s still propaganda.

The first college that I attended was designed to integrate living and learning spaces, so there were classrooms in the dorms, dorm rooms in the academic and administrative buildings, and a number of buildings, like Andrews, which were in fact houses, with classrooms on the first floor and bedrooms housing students upstairs. My first semester, I took a literature seminar which met in the morning in a classroom in Andrews House, and we would occasionally see members of the “Posse” stumbling around, hung over.

I don't love smoking, but I loved this essay.