Domestic Left #75: Who will our next oppressors be?

Dune, race, and democracy

In a voiceover during the opening of Dune Part 1, which came out in 2021, a woman’s voice asks “Who will our next oppressors be?” The voice belongs to Chani Kynes, played in Denis Villeneuve’s film by Zendaya.

The sequel, Dune Part 2, which completes the story of the first Dune novel, came out this past spring. Villeneuve has done a masterful job of translating this complex novel into, well, two compelling films. Making novels into movies is no easy task, but Villeneuve does a good job of using movie conventions to tell a novelistic tale, reorganizing the story’s structure while maintaining the essential flow and, well, directing it into a simpler but still compelling narrative. Similarly, he has collapsed the complex ideas from the book in a way that made them intelligible without doing violence to them. And he has avoided any trace of John Hughes-ness in the teenage romance between Chani and the films’ hero, Paul Atreides, and largely kept in check the insatiable desire of modern screenwriters to insert snappy ironic dialog everywhere.

Well, I think he has accomplished all of that. It’s hard to know, because I have read the original novel three times (though, admittedly, the most recent time was close to 20 years ago), and all of the subsequent novels, most of them twice.

In the communications trade, there is this concept called “the curse of knowledge.” The curse of knowledge is that, once you know something, it is no longer possible to know what it is like not to know it. Therefore, it is extremely difficult to understand how, say, a movie will be understood — or misunderstood — by anyone who does not already know the things you know.

The first Dune novel, which was published in 1967, contains at least three major “science fictions,” or fictional speculations about the future development of science, all of which have major implications for the plot but not all of which are explicitly dealt with in the movies. (I think; again, the “curse of knowledge” makes it somewhat difficult for me to tell, from a single viewing, the degree to which these concepts are in fact explained.)

Perhaps the most well-known, and I think the most well-explained in the movies, is the dependence of interstellar travel on a mind-altering drug known as “spice.” Spice is harvested on the desert planet Arrakis, known to its indigenous inhabitants, the Fremen, as “Dune.” This, naturally, makes spice an incredibly valuable commodity (not unlike, say, oil ... draw your own parallels), and much of the plot revolves around conflict between two “Great Houses,” the (good) Atreides and (evil) Harkonnens, over control of the planet, and thereby the spice.

The harvesting of spice is a treacherous endeavor, as the very creatures which produce the spice, the giant sandworms which roam the desert, are attracted to the rhythmic sounds of the massive mechanical spice harvesters. Spice-harvesting crews must be constantly on the lookout — it is always a matter of when, not if, a worm will appear. In addition, the Fremen often launch armed raids on spice-harvesting operations, part of their ongoing guerrilla warfare against whichever Great House has been assigned to rule over them by the distant galactic “Padishah Emperor.”

What is somewhat less explicit in the Villeneuve movies is why spice is so important to interstellar travel. The second “fiction” here concerns the “Butlerian Jihad,” waged after humans were enslaved by “thinking machines.”1 Following this war, humanity embraced a complete prohibition on, essentially, computers2, and instead began intensively training special cadres of humans to specialize in performing what we might consider “superhuman” tasks. “Mentats,” for example, are trained to perform complex calculations in their heads, and are often employed by the heads of Great Houses as advisors.

Like every sci-fi world that envisions a multi-planetary empire, Herbert’s universe requires that faster-than-light travel be possible. In Dune, the human cadre that pilots “heighliners” between star systems are known as the Spacing Guild, and they rely on the prescience (ability to see the future) granted by spice in order to get their spaceships safely through the “folding” of space.

Other people use the spice as well. The aristocracy of the Great Houses take it in small amounts for its life-prolonging properties, and the Fremen on Dune are constantly exposed to it. But most notably the Bene Gesserit, a quasi-religious sisterhood of which Paul’s mother Jessica is a member, use a spice-adjacent product, the “water of life” created by drowning a young sandworm in water, to create “Reverend Mothers.” These often creepy figures (early in both the book and film a Reverend Mother subjects Paul to an extremely cruel test) are elders of the order who gain both genetic knowledge of their female ancestors and a certain amount of prescience from the drug.

The third “fiction” concerns the importance of hand-to-hand combat. Villeneuve doesn’t really have to explain this, because we now live in the sci-fi imaginary created by Star Wars, a series of films that owes more than a little to Dune. The light-saber battles that were a marvel of imagination and special-effects when they were created by drawing directly onto film in the 70s, and then multiplied into a veritable forest of futuristic CGI fencing in the prequels, have normalized the idea of swordplay in science fiction.

But when Dune was written in the 1960s, laser guns reigned supreme in hard sci-fi, and Herbert does not grant his hand-to-hand fighters the effectively supernatural power of Jedis, who can deflect laser-gun blasts with their light sabers. Instead, he posits the development of force shields which dramatically slow the velocity of anything which tries to enter them — and which, if they come into contact with a laser, create enormous, uncontrollable explosions. So laser guns are effectively out of the question, and projectile weapons ineffective (a bullet would be slowed to non-lethal speed by the shields) — the only way to effectively fight someone with a shield is to get close enough to them to force your knife slowly through their shield, then wield it quickly and expertly enough to kill them.

This allows Herbert to set his drama in a setting that is in many ways pre-modern. Not for nothing does he name the heroic Great House “Atreides” — they claim descent from none other than Agamemnon, of the Iliad — and the Great Houses, the Emperor, the Bene Gesserit, and the Spacing Guild all jockey for power in what is essentially a feudal social order.

But that order is held together, and in some ways negotiated, through a kind of state-capitalist “joint stock” company called CHOAM, which distributes the profits of the spice trade among the various players. It is a feudal society, but it is also reminiscent of the kind of state-led capitalist economies which dominated much of the world in the middle of the 20th century.3 In other words, the kind of political economy in which Herbert was writing.

I am not really that interested in writing about how cultural products figure into the “culture wars,” but I do find it fascinating that a film about a work that is so deeply political seems to have provoked so little controversy. (I mean, you can Google “woke Dune” and find people yelling online, but so far as I can tell it hasn’t made it into the mainstream of right-wing media. And liberals by and large don’t seem to have found anything “problematic” about it in the mainstream-mainstream media. Despite, um, all kinds of problematic stuff.)

In part I suspect this is simply because Dune fandom is based on books; no one has a beloved childhood memory of watching Max von Sydow play Liet-Kynes, the imperial “planetary ecologist” and Chani’s father, in David Lynch’s widely-panned 1984 film adaptation, so seeing the character portrayed by a Black woman is just not a big deal.

But at a deeper level I think it is because the Dune universe is so thoroughly imbued with a kind of essentialism (or pessimism) about race and sect that sits well with both the right and center-left in our contemporary discourse.

Like so much else in the movie, this aspect of the books is there, but handled with such a light touch that it is not obvious. The character of Dr. Yueh is a good example of this. To a casual moviegoer, he can appear as simply the Atreides family doctor, who happens to be ethnically Chinese (and with whom Paul briefly speaks Mandarin). He is a tragic figure who betrays the Atreides because the Harkonnens have kidnapped and are torturing his wife, but who makes it easier for Paul and Jessica to escape and gives Paul’s father, Duke Leto, a secret weapon to take revenge on the Harkonnens as he dies.

Readers of the books, however, will know that the Atreides never questioned Yueh’s loyalty because he is a “Suk doctor.” The Suk doctors are a cadre of Asian-coded physicians who have been “conditioned” to never betray a patient — thus making it safe for those atop the intrigue-filled feudal world of Dune to trust them with their health. (Villeneuve’s soft-pedaling of this particular plot point is probably wise: while kidnapping and torturing someone’s wife may have seemed like the kind of unspeakably vile thing that only the Harkonnen could imagine when Herbert wrote Dune in 1967, I feel like any two-bit gangster in a Quentin Tarantino movie could break a Suk doctor in like two minutes, rendering the “conditioning” laughable in a modern moviegoer’s jaded eyes.)

The books also include an account of the Tleilaxu, a creepily Orientalized race of people who get around the Butlerian prohibition on machine technology by breeding “gholas” (a type of clone) and “face dancers” (individuals who can modify their own appearance to perfectly mimic others) in their “axlotl tanks,” which are eventually revealed to be the wombs of Tleilaxu females kept in a vegetative state. (The Tleilaxu are barely mentioned in the first novel, but they figure heavily in the second one, so it will be interesting to see how Villeneuve handles them if he makes another sequel.)

The racial essentialism of the books comes through most clearly in the movie’s treatment of the Harkonnen, in a way that is particularly congruent with modern liberal racial pessimism. In the novels, the Harkonnen are coded as evil not only through their cruelty but through their German- and Russian-sounding names (the Baron’s first name is Vladimir; the “twisted mentat” who derives the plan to break Dr. Yueh’s conditioning is named Piter de Vries), and the obesity and homosexual proclivities of the Baron (the former is retained in the movies; the latter, thankfully, dropped).

In Dune Part 2, a dramatic scene on the Harkonnen home world of Giedi Prime is filmed in full Leni Riefenstahl triumph-of-the-will black and white. The Harkonnens, all pale and shorn of any hair, fill a massive stadium in their thousands, chanting their bloodlust as they watch the Baron’s cruel and sociopathic nephew slaughter drugged Atreides fighters in hand-to-hand combat.

This is what I mean by the essentialism/pessimism of the film. One simply cannot imagine a Harkonnen child developing a conscience and joining the Atreides.

The obsession with genetic inheritance is even more clear in the Bene Gesserit breeding program which forms an important part of the plot. For centuries, the Bene Gesserit have been using both marriage and seduction in an attempt to breed a “Kwisatz Haderach,” a kind of prophet. The Kwisatz Haderach is a man who can drink the water of life and survive, becoming a kind of male Reverend Mother but one who also has access to the genetic memories of his male ancestors — along with a terrifying amount of prescience.

Paul’s mother had been ordered by the Bene Gesserit to have a daughter to further the program, which is close to completion. But she fell in love with her assigned husband, Duke Leto, and he wanted a male heir — so she had a son instead. (Bene Gesserit can control the sex of their children at conception.)

Against the backdrop of the great-power conflict between the Atreides (who form an alliance with the Fremen, who then take in Paul and Jessica after the rest of their house is wiped out) and the Harkonnen (who are secretly being supported by the Emperor), Paul wrestles with what it would mean to become the Kwisatz Haderach — a charismatic leader with an amount of personal power no human being has ever had before. He foresees a holy war in which his legions of fanatical Fremen (yes, there is some Orientalism at work here) spread his rule throughout the galaxy, slaughtering billions of human beings in the process. He goes ahead with it anyway.

Dune is a deeply conservative work — though, like all great works of art, it contains numerous contradictions, and can be read in various different ways. (Among other things, it introduced ideas about ecology that we now take for granted, but which at the time were quite radical, into science fiction and, in many ways, the broader culture.)

As Substacker Freddie deBoer points out, one of the key things Herbert is up to in the series4 is

dramatizing the way that people fall for phony messiahs and false prophets, showing how this human tendency has destructive consequences. And that too is text, not subtext: the Fremen believe that Paul Atreides is the messiah, the Lisan al-Gaib, only because the shadowy cabal that is the Bene Gesserit have seeded the galaxy with invented messiah stories as an open-ended tool for control.

Which is incontrovertibly a real human tendency — and one with often disastrous consequences. Herbert is said to have been inspired in part by the National Liberation Front in Algeria, which spearheaded that country’s anti-colonial independence struggle and, well, was hardly a model of democratic and progressive governance during its almost three decades ruling an independent Algeria as a one-party state (though, as is so often the case, the alternatives turned out to be worse.)

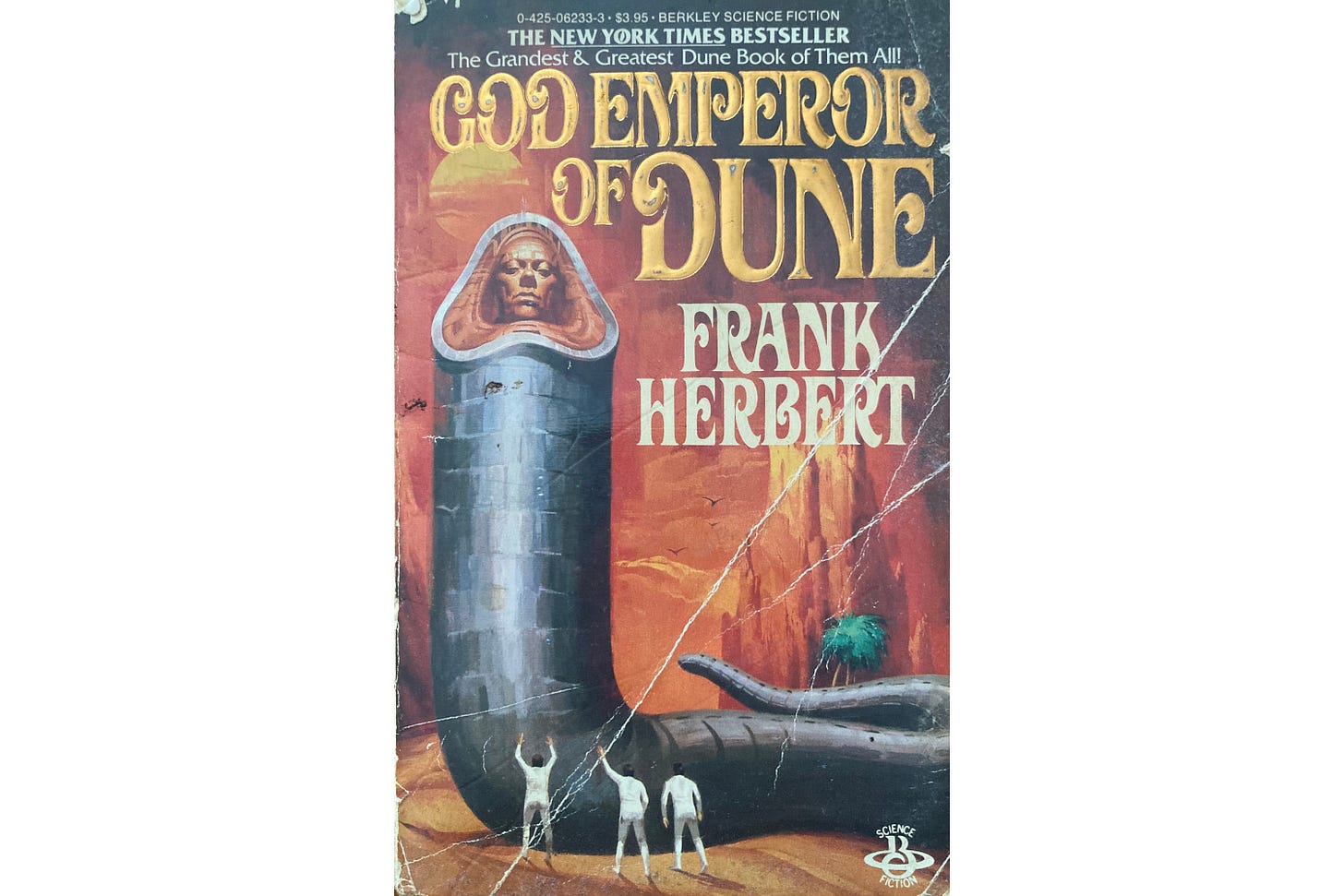

But the problem with the Dune novels is that they present no democratic alternative to fanaticism, no vision of self-liberation. Paul and his successors (at the end of the third novel his son Leto II covers himself with sandtrout, an embryonic form of sandworm, which turns him into a man-sandworm hybrid and allows him to rule Dune, and the universe, for 4,000 years as a “god emperor”) replace the feudal-state capitalist social order of the previous Empire with an authoritarian theocratic state. Paul and then Leto II hold absolute power, their dictates enforced both by their godlike power and by legions of religiously devoted warriors, first the Fremen then the all-female “Fish Speakers” who do Leto II’s bidding. It’s hard not to see in this the kind of Cold War warning that if you try to change things for the better, it will only result in totalitarianism.

While thinking about the conservatism of Dune, I have repeatedly been reminded of the ideas laid out in political theorist Corey Robin’s book The Reactionary Mind. Robin’s book, a brilliant survey of conservative thought which, unlike most left-wing critiques, takes that thought seriously, argues essentially that since the democratic revolutions of the 18th century (most notably, the French revolution), conservatives have been unable and/or unwilling to argue explicitly for a return to, well, the ancien regime, a system in which strict social hierarchy was enforced and justified by God’s will, God having explicitly created all men (let alone women and children) unequal.

Instead, Robin argues, conservatives have justified their calls for restoring hierarchy through a quasi-populist critique of the “elites” that run (imperfectly) democratic societies5 (sound familiar?) in the name of the individual, especially the exceptional individual — e.g., John Galt in Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged.

The elites of liberal societies — even the ones whose politics are, in fact, conservative — are derided by conservative ideologues as, above all, “soft.” From Edmund Burke to Clarence Thomas, the reactionary venerates (and, presumably, believes him or herself to be one of) those who have earned the right to dominate others through “native intelligence and innate strength.”

Unlike the feudal past, where power was presumed and privilege inherited, the conservative future envisions a world where power is demonstrated and privilege earned: not in the antiseptic and anodyne halls of the meritocracy, where admission is readily secured ... but in the arduous struggle for supremacy.6

This veneration of trial by adversity permeates the Dune universe. The power of the Galactic Empire rests on an elite military force known as the “Sardaukar.” The Sardauker possess exceptional fighting skills (and brutality, and fanatical devotion to the Emperor) because they are trained in the unforgiving environment of Salusa Secundus, an entire planet that serves as an imperial prison. Paul is able to defeat the Emperor in large part because he makes an alliance with the Fremen, who are even more skilled fighters than the Sardauker on account of living in an even more harsh environment than Salusa Secundus. And Paul’s acceptance by the Fremen comes, not from careful negotiations or discussions of mutual interests and strategic alliances, but because he defeats — and kills — a Fremen man in a knife-fight.

I have read the majority of the Dune novels twice, and Dune itself three times. The first time, as a pre-teen, all I really took away from them was the world-building, and — other than a minor quibble about the portrayal of technology7 — the movies do a fantastic job of building a cinematic version of that world.

The second time, in college, I read Dune as an allegory about mind-expanding drugs, because, well, that’s what I was really interested in at the time (though more as a thing I read about than a thing I actually did). The idea that you could take a substance that would give you supra-rational insight into the world, the future, the secret ropes and pulleys that push and pull the events of history, was extremely appealing.

It was only on my third reading of all six novels (the last two of which had not yet been published when I first read the series), sometime during the George W. Bush administration, that I really understood them to be about politics and power — which is, of course, what I have been writing about here.

However, I remain nostalgic for my experience of the first four books, and maintain that, regardless of Herbert’s intentions, they form a tighter story arc with better closure at the end. (To be fair, Herbert never finished the seventh novel with which he intended to close the series. His son and another writer have jointly written a seventh and eighth novel, supposedly based on Herbert’s notes, but I have not read them.)

That story arc is about ecology. When we, as it were, arrive on Dune in the first novel/movie, it seems an inhospitable place. The Fremen survive only by wearing “stilsuits” which capture every bit of their body’s discarded moisture, from sweat to urine, filter it and reclaim it as drinking water.

But the planetary ecologist Liet-Kynes has discovered that the planet in fact has massive reserves of water. In both the book and the movie, s/he shows the Atreides secret laboratories in which s/he is developing a program, along with the Fremen, to recapture that water.

During Leto II’s four-millennia reign, that program is carried out, and Dune is transformed into a lush, green paradise, untroubled by sandworms. (Leto II’s absolute, smuggler-free control over the remaining stores of spice becomes, naturally, another lever of power.) The Fremen, once hardened into the fiercest warriors in the universe by life in the unforgiving desert, become soft.

At the end of the fourth novel, God Emperor of Dune, Leto II allows himself to be assassinated by a plot that he, thanks to his prescience, had foreknowledge of. But he also had foreknowledge that this was the best path for humanity, to release it from his own tyranny. His dying body shatters into sandtrout, which, we are told, will reclaim the planet as desert, and repopulate it with sandworms — though these new sandworms, all being descendants of the God Emperor, are not the blind, atavistic, destructive sandworms of old, but a new version, each imbued with a fragment of human consciousness. It is an ending both cyclical, with the once-desert paradise planet returning to desert, and progressive, with Leto having set humanity free from the curse of the prescience that turned his father into the Kwisatz Haderach and him into a giant monstrosity.

Out of Herbert’s sprawling epic about the massive, almost impersonal forces of political power and ecology, Villeneuve does his best to create a film that, at least superficially, lives inside our modern democratic ethos. And I think for the most part he succeeds. Largely thanks to Chani.

The character of Chani, a relatively minor one in the novels if I remember correctly, carries a lot of water in the films, especially the second one (something Zendaya pulls off exceptionally well). She is, of course, the love interest, and she is also the sassy woman of color who teaches the privileged white boy how to survive in the desert.

Being the child of an (unspecified) Fremen and the imperial off-worlder Liet-Kynes, Chani is also a bridge character between the Western-coded imperial culture of the Atreides and the Fremen, whose are portrayed as noble but, well, still kind of savage. (Liet-Kynes’s being a Black woman instead of a white man in the films also presumably makes the character’s “going native” less problematic to modern progressive audiences, who are more attentive to the dynamics of skin color than of imperial power.)

But most importantly, Chani brings in language that does not come from the books, but which frames them in, I think, a helpful light. In the voiceover that opens the first firm, “Who will our next oppressors be,” she names the Harkonnen not simply as enemies but as oppressors. The Atreides, too, are presumed to be oppressors as a matter of structure, not of character — and, arguably, only their near-total obliteration at the hands of the Harkonnen, which forces them to relate to the Fremen as supplicants rather than benevolent overlords, mitigates their status as oppressors.

In the second film, Chani says that the “Fremen will liberate ourselves” — a line that I am certain does not come from the original text. If the concept of oppression is not well-developed in Herbert’s books, the concept of liberation — and certainly of collective, rather than simply individual, liberation — is completely absent.

In this, I think Villeneuve’s films demonstrate a good approach to the fact that lots of great art is, in modern parlance, “problematic.” There is a tendency, in progressive circles, to either dismiss the artistic value of works whose politics we find troubling, or to bend over backwards to find other readings more to our liking. Villeneuve does neither: he leaves all (or at least most) of the troubling and often contradictory politics of Dune intact, but helps us to see them through a different pair of eyes, and to ask a different set of questions than the novels do. When we exchange one set of rulers for another, more benevolent set, are we simply moving on to a new set of oppressors? And, more importantly, how do we liberate ourselves?

As I worked on this piece over the past six months or so, I often wrestled with the question of how a democratic ethos can be represented in film, an art form with a structural tendency towards highlighting a small handful of strong characters, or even just a single hero or anti-hero, against backdrops of (in battle or crowd scenes, for example) uniform masses. In other words, towards a sort of emotional autocracy, or at least oligarchy.

Although I haven’t seen the film (not really my cup of tea), I think Freddie deBoer’s short essay about Mad Max: Fury Road does a pretty good job of answering that question.

A couple of other, mostly unrelated things I’ve enjoyed reading this week:

Richard Powers’ novel The Goldbug Variations came out when I was in college, and my more literarily-inclined friends raved about it. A dozen years later, I finally read it myself and understood why. Powers has a new novel out this coming week, and there was a nice piece about him in The Guardian.

“On the one hand, poetry is secret and natural, on the other hand it must make its way in a world that is public and brutal.” Maggie Doherty writes about how the Irish poet Seamus Heaney dealt with The Troubles in The New Yorker.

“A new start after 60: it took 70 years to find my inner artist. At 82, I’m in my studio every day” (The Guardian)

Australian singer-songwriter Emily Barker’s new album Fragile as Humans has been on repeat on my laptop over the past week, after I purchased the album on Bandcamp. But you can also check it out on Spotify:

And she has made a nice lyric video for the opening song, “With Small We Start”:

As an aside, the large-scale pattern-recognition algorithms currently being passed off as AI are not actually intelligent, and will not enslave us. They will, however, probably kill us all by contributing to the warming of the planet through the massive amount of processing power they require.

Though it is also difficult to imagine some of the technology in the Dune universe functioning without computers, especially the remote-control flying poison dart that almost kills Paul early in the film and novel.

Many historians would argue that this was also a feature of the political economy of the U.S. from the 40s through the 70s; although in the U.S. corporations were much more powerful vis-a-vis the state than they were in France, they still used the state in a similar manner.

Which he does, brilliantly. As deBoer points out, the novel — and the films — are extremely effective at sweeping the reader/viewer up in Paul’s cause. The linked article is called “Screw You Guys, I Root For Muad’Dib” (“Muad’Dib” being the name Paul adopts when he is taken in by the Fremen) and I absolutely, 100 percent agree. Like deBoer, “I’ll follow Muad’Dib anywhere. Paul and his rebel army are cool as fuck. He shall be Padishah.”

This is why the centrist neoliberalism of the Clintons and Obamas, which explicitly relies on a technocratic elite, and which closes off democratic possibilities by subjecting everything to the market, is so vulnerable to right-wing populism.

Corey Robin, The Reactionary Mind (Kindle edition), pp. 33-34.

In the books, machinery in the post-Butlerian Jihad world is for the most part small and brittle. Villeneuve can’t resist making it large and imposing, if gritty and metallic. Which makes for good cinematic scenes, but also, I think, undermines what is arguably the core story arc of the original books: the conflict between the human and the technological.

This was interesting. So I’ve never fully read any of the Dune novels but many people I know are obsessed with it so I know a lot about the lore and story.

One thought I have is that the pessimism of the Dune universe is what makes it so adaptable as a board game. There are two different versions. One from the 70s and another from a couple of years ago. While the experience is different the concept is similar. They are both political, strategy games where you play as a faction (one of the houses or other major players like the Bene Gesserit or Spacing Guild) with the goal of domination. There is no option outside of being the one in charge and each faction plays differently due to their inherent powers/characteristics.

Another thought is that the gender politics of Dune is fascinating but also still both pessimistic and essentialist. I really appreciated the prominent role that women had in Dune especially because sci fi is not always known for it's portrayal of female characters. It’s notable that the Bene Gesserit are so powerful and control so much of politics. But their power is undercut by the fact that they are so secretive and that their ultimate ruler has to be a man. It’s notable a group of woman has such power but it doesn’t seem like there’s a vision where women could be in charge openly (though I don't know their role in the later novels).

Just dropping by, but ...

A very interesting take on the politico-cultural themes in Dune. Particularly the theme of "state capitalism". Dune was published in 1965, and I remember reading (some time after 1975!) that the US economy was dominated by the same industries in 1975 that it was in 1925, each industry was dominated by the same few companies, and each industry was unionized by the same union. Each industry had a bureau of the Commerce Department to help it coordinate growth so there wouldn't be "overcapacity". There wasn't any visible alternative, western Europe was much the same, and Communism was a monolithic version of the same thing that delivered worse results.

And it wasn't a bad deal for ordinary people. I've noted a quote from Pocatllo, Idaho mayor Roger Chase, "When I grew up in Pocatello, you could not read or write and still get a job at the railroad making $50,000 or $60,000 a year." (I suspect the amount of money is incorrect, given inflation, but the point remains that you could live well even being illiterate.)

Most of the protest movements since then seem to have wanted to *go back* to those times so that good incomes could be had by people of modest education. The proposed techniques differ between the left and the right, but none of them make clear how to do it without disconnecting from world trade entirely and throwing out 50 years' development of automation.

As for "Though it is also difficult to imagine some of the technology in the Dune universe functioning without computers, especially the remote-control flying poison dart that almost kills Paul early in the film and novel.", remember that if a human is guiding it in real-time, you don't need a computer. "Wired and wireless remote control was developed in the latter half of the 19th century to meet the need to control unmanned vehicles (for the most part military torpedoes)." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remote_control#History But these days it's hard for people to imagine!