Yesterday, I gave the following remarks at a panel on “Labor, Technology, and the Cold War” at the 2025 Labor and Working-Class History Association conference in Chicago — the second (!) academic conference of the year at which I have presented. Since some of these remarks assume a certain level of knowledge of labor history (and acronyms), I have added footnotes to hopefully make things reasonably clear for the more general reader.

Following the postwar strike wave of 1945-46, General Electric President Charles E. Wilson famously said that “The problems of the United States can be captiously summed up in two words: Russia abroad, labor at home.”

This quotation is often invoked by labor historians, and indeed by us in UE1, to make the point that militant, class-conscious trade unionism was just as much a target of the Cold War as was the Soviet Union. But we tend to invoke it in the context of what I think is a widespread assumption: that the Cold War was, essentially, a geopolitical conflict between two great powers, the U.S. and U.S.S.R., one that capital took advantage of in order to suppress the left wing of the labor movement.

But Charles Wilson didn’t suggest exactly that; he proposed that “Russia” and “labor” were two co-equal problems for capital (which of course he conflated with “the United States” because that’s how capitalist hegemony works).

The proposal I want to make is that we look at the Cold War, not just as a geopolitical conflict between states, but as an initiative of U.S. capital to use the power of the federal government to expand its control of not only territory and ideology but also the workplace. Or, to put it another way, that capital’s insatiable desire to expand its control over the productive capacity of people and the planet drove both the geopolitical conflict with the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc — which, regardless of what you think of them, incontrovertibly did remove productive capacity from the control of capital — and capital’s quest to control labor at home.

Looking at it this way, I think, helps us to see the connections between state repression of the labor movement and technological innovation — specifically efforts to automate the workplace in the 1950s.

Interestingly, in opening what became a two-day discussion about automation during the 26th UE Convention, in 1961, UE Secretary-Treasurer Julius Emspak located the origins of federal subsidies for corporate research and development in the federal government’s effort to get companies to convert to war production during World War II. He told delegates:

In 1942 one of the biggest prices they [corporations] extracted ... was that they get research and development contracts on a cost-plus basis and that whatever patent, process, method, whatever they learn, the company retains the exclusive commercial benefits for it.

But in order to make the most profitable use of the new technologies they were developing, capital needed to eliminate the kind of militant unionism practiced by UE and the other “left-led” unions in the CIO: the Farm Equipment Workers, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union on the West Coast, Mine, Mill, and so forth. These were unions that would challenge both corporate control on the shop floor and corporate control over the economy as a whole.

As Toni Gilpin demonstrated in The Long Deep Grudge, her book on the Farm Equipment Workers, the political radicalism of FE leaders led them to practice a form of unionism that contested the boss’s power on the shop floor as much as in contract negotiations. As FE Director of Organization Milt Burns famously said, “the philosophy of our union was that management had no right to exist.”

On a larger scale, Rosemary Feurer, in Radical Unionism in the Midwest, showed how UE District 8 mobilized worker and community support during and after World War II for a planned conversion to a peacetime economy. The St. Louis-based District 8 proposed the establishment of a “Missouri Valley Authority” which would have broad authority to engage in economic and environmental planning for the region.

To give a quick flavor of how those implementing automation felt about left-wing unions, in the early 80s one of my predecessors at the UE NEWS had a brief correspondence with the author Kurt Vonnegut. Vonnegut had worked in the publicity department of the GE Turbine Shop in Schenectady, New York in the late 40s, an experience that informed his first novel, Player Piano. The engineers at the plant, he recounted in the correspondence, considered UE to be “the devil incarnate.”

As is probably well known to most people here, the federal government and the companies joined forces in the late 40s and into the 1950s to remove such “devils incarnate” from plants across the country, with the shameful cooperation of the AFL and much of the CIO.2 UE was replaced by the IUE3 at the Schenectady plant in 1954 after the FBI leaned on the local president to switch his allegiance.

By the late 1950s the fully-automated future explored in Player Piano seemed to many to be on the way. Technology had progressed to the point where it became feasible and cost-effective to produce even relatively small numbers of specialized parts with automated machinery, and GE was boasting that its Schenectady plant was “The largest automated job shop in the world.”

In June of 1960, the UE NEWS interviewed three leaders of UE Local 1111 at the Allen-Bradley plant in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, about what automation meant in their shop. Chief Steward Robert Gaulke told the paper how machines which automatically classify potentiometers had eliminated seven of eight jobs in one department, and how the installation of a pneumatic tube system to deliver parts to different departments had eliminated the positions of almost eighty workers. As the UE NEWS reporter editorialized, “A little multiplication provides startling proof of the tremendous money made by A-B on this single switchover.” Or, more succinctly, “Fewer jobs; more money for boss.”

Local 1111 President Herman Kuehne concluded that the local, and the union as a whole, needed to fight for a shorter work week with no loss in pay and to establish workers’ right to what he called “real wage security.”

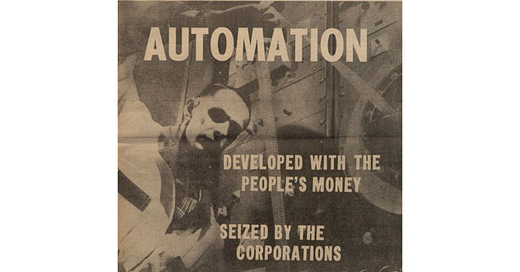

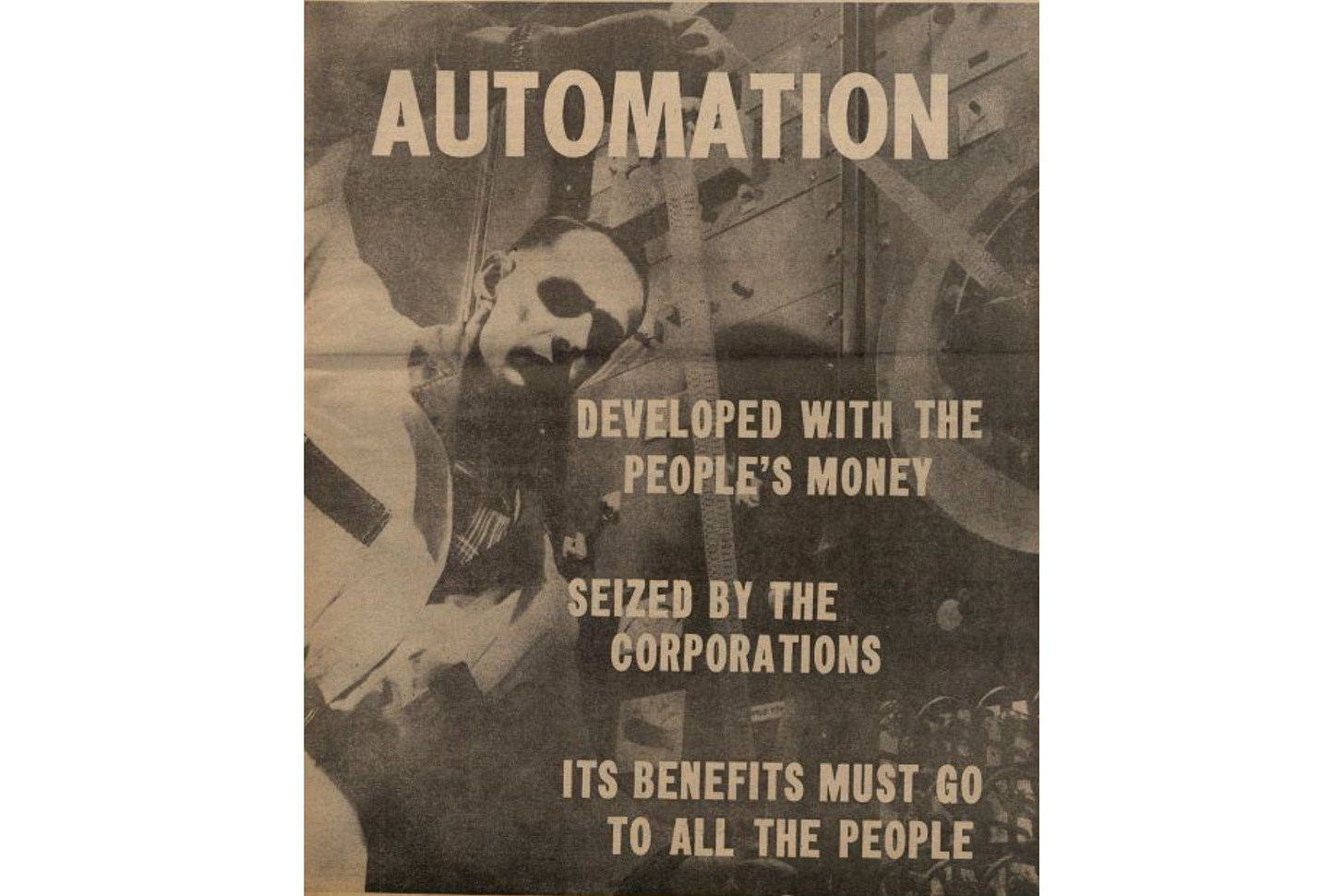

The National Union took up these questions in 1961 in a special issue of the UE NEWS on automation. The paper pointed out that virtually all of the research and development that made automation possible had been paid for by the federal government, either directly through grants or indirectly through tax credits, essentially descendants of those World War II-era cost-plus contracts.

“It is our job in UE,” the editors wrote, “to propose and fight for measures to give the workers of industry a rightful share of the benefits of automation.”

The measures proposed by the UE NEWS, and adopted in resolution form by the 26th convention later that year, included increasing the minimum wage from $1.15 to $3 per hour (which would be over $30 per hour in today’s money), shortening the work week to 35 hours with no loss of pay, and federal legislation mandating that companies bargain over the introduction of all new machinery.

Needless to say, we did not win the shorter work week, or any other part of this program, but it’s worth noting that one, we were willing to think in big, broad terms about what capital as a class owed society as a whole and two, we were interested in contesting the introduction of technology at the shop level. This stood in sharp contrast to the approach of most of the rest of the labor movement, who, if they addressed automation at all, mostly did so at the level of ameliorating its effects on their members through contractual benefits in their own industries.

To return to my original theme, I think looking at the Cold War as a corporate project of workplace control helps us see the connections between military adventures, repression of dissent, and technology. It also helps us see how the most effective vehicle for resisting that, for fighting for peace, civil liberties, and humane technological development, is a labor movement rooted in contesting control of the workplace, and in asserting workers’ right to master and own the world we have built, and continue to build.

Filed under: History

This morning, I am flying from Chicago to San Francisco, where I will embark on a nearly two-week vacation through northern California and southern Oregon, traveling — and sleeping — in a borrowed van. While not exactly primitive, this will be the most extensive experience with outdoor living in my life so far ... so wish this city boy luck.

I don’t expect to have much if any access to the internet, so I probably won’t be able to acknowledge replies or comments until I get back to civilization at the end of the month. I have scheduled a post for next week, though, and will be back on the 29th with, I hope, some account of my adventures. Or at least photos. See you on the flip side!

UE is the abbreviation for the “United Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers of America,” the labor union I have been a member of most of my adult life, and for which I have been working as Communications Director since 2017. Historically, UE represented workers in electrical manufacturing (e.g., companies like General Electric and Westinghouse), but in recent decades has expanded to organize workers across a wide variety of economic sectors.

UE is perhaps most well-known for the persecution we suffered during the Cold War, when we were accused of being “communist-dominated” and lost the majority of our membership to raids by other unions.

The CIO, or Congress of Industrial Organizations, was formed in the mid-1930s to organize mass-production industries on an “industrial” basis — e.g., organizing all workers in the industry into one union. This was in contrast to the older, more conservative American Federation of Labor (AFL), which organized workers by “craft” (e.g., electricians in one union, machinists in another, carpenters in a third, etc.). The most well-known CIO unions are the United Autoworkers and United Steelworkers.

In 1949 and 1950, the CIO expelled eleven unions, including UE, for “communist domination,” and CIO unions proceeded to regularly “raid,” or attempt to replace, UE and other expelled unions. These raids were frequently assisted by the federal government in various ways, such as bringing the House Un-American Activities Committee to town to subpoena UE leaders immediately before the vote.

The CIO merged with the AFL in 1955 to form the AFL-CIO.

The International Union of Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers, or IUE, was created by the CIO in 1949 explicitly to replace UE. It is frequently referred to by our members as the “Imitation UE.” The IUE merged into the Communication Workers of America in 2000.

Outstanding! This is a really brilliant, insightful presentation (which would be true even if you didn't cite my correspondence, a fact which underscores my dual character as both historian and historical artifact).

If only the UE had won then maybe the US would be in a better position to navigate how to best implement automation without destroying people's livelihoods or making worse products.

Sounds like it'll be an amazing trip!