I woke up

with a poem half-remembered in my head

the other night.

I could not

for the life of me figure

how it got there.

I do not

read much poetry.

In the summers of my early teenage years, when I had plenty of time and nowhere really to go, I would stay up all night in the kitchen, listening to the overnight jazz programming on KANU, reading science fiction, eating chips and salsa, and vaguely fantasizing about a bohemian adulthood living out of a van. I couldn’t say where this fantasy came from — I hadn’t yet graduated to reading On the Road or anything like it — but I think the key aspect of it was imagining a life in which I could still spend all night reading.

The night after I graduated from high school, I stayed up all night at Village Inn drinking coffee with my friend P, who still had another year of high school before him. We talked about the future. He told me he was sure that within our lifetimes we would be able to plug computers directly into our brains. He also advised me to elope with my poet girlfriend.

In a corner of the Scaife Galleries at the Carnegie Museum of Art is a room called Night Poetry, full of “rarely seen works from the darker recesses of the collection” which promises “shadowy scenes and obscure figures” and “a mood of mystery and unease.” The lighting is somewhat lower than in the other galleries, the walls are painted a dark, slightly purplish gray, and many of the works make prominent use of the color black and other dark hues. The artworks, we are told, are inspired by “dreams, hallucinations, visions, and nightmares.”

I don’t know how much my teenage fondness for staying up all night was due to “insomnia” and how much of it was due to caffeine (or to the asthma medicine, essentially low-grade speed, that a bandmate and I would periodically use off-label during all-night songwriting sessions the summer after I graduated). Simply not going to bed isn’t really insomnia anyway, or at least it has never seemed so to me.

No, the much worse kind is when you wake up at 3am, not fully rested but unable, for the life of you, to get back to sleep. As Adam Gopnik wrote recently in the New Yorker:

Few phobias can be quite as psychologically painful as sleeplessness. The body simply won’t lose consciousness, and losing it is something that cannot be willed into existence, or, rather, into nonexistence. And so one begins to envy desperately not just the sleeping spouse but everyone in the world who is not awake.

That kind of insomnia came into my life in my early 30s. Prior to that, when my children were very small, I was probably so exhausted from chasing them around all day (I was the primary caretaker) that I had no trouble sleeping through the night. Once they began attending school, I not only lost the benefit of physical exhaustion, but I gained a morning deadline — I had to be up by 6am or so to feed them, get them ready, and get them there. So I would wake up at 3am, and, as the minutes and then hours ticked by without being able to get back to sleep, I would anxiously count down the amount of potential sleep remaining: two hours, one hour, maybe half an hour if I’m lucky.

Manuel Rivera’s Metamorphosis [Homage to Kafka] is mounted on the wall like a painting, and it is, I suppose, painted, but it also has a three-dimensional element to it. It consists of two layers of metal mesh screen (like the kind your screen door is made of) mounted on wires strung from wood dowels that protrude from a wood panel. The screens are painted, mostly black, though there are also some dark browns.

It projects maybe four or five inches from its wood “canvas” and the layering of screens over each other gives it a weird iridescence, like an insect’s mosaic eyes, especially as you move towards it, or turn your head back and forth. And the way the scraps of screen that forms its top layer are arranged is indeed reminiscent of a cockroach’s carapace.

It has been over 35 years since I read Metamorphosis, so I don’t remember much about it, but Rivera’s piece captures well what I do remember: a sense of being trapped, not just physically, but by some force beyond your control that has wrought some inexplicable change in you that you are powerless to reverse. Not unlike insomnia.

Even on a good night, I wake up a lot, frequently because I need to get up to use the bathroom. (A weak bladder runs in the male line of my family.) Most of the time I fall right back asleep; sometimes I have what I have come to think of as a “small insomnia,” in which I lie in bed awake for maybe 10-20 minutes but then fall back asleep. And sometimes I have a “big insomnia.” Those rarely last less than two hours, and can often stretch out for more than three.

Needless to say, I have tried all kinds of strategies to keep my insomnias “small,” to train myself to slip back into sweet unconsciousness.

The first strategy that was successful grew out of my realization that my dreams often occur in a particular geography, a particular landscape, with specific recurring places in specific relationship to each other. It is structurally similar to my hometown of Lawrence, Kansas — there is a river running northwest-to-southeast across the northeast corner of town, a downtown running south from the river the way Massachusetts Street does in Lawrence, and a commercial street with an auto repair shop running west like 6th Street does. But it also has a district clearly inspired by the dorms I lived in my junior year of college (placed on a hill north of 6th street — which is weird because there are no hills north of 6th in Lawrence and the dorm in question was on some of the flattest land in Iowa), and a small collection of buildings near a railroad clearly reminiscent of the southern part of Iowa City, where I lived for three years after graduating from college. And some parts of it are completely sui generis — a sort of indoor mall like no place I have ever been before, a coffee shop/newsstand roughly where a parking lot sits in Lawrence.

I found, at least initially, that by imagining myself in these places I had been before in dreams, I could often drift back into them. It seemed miraculous, like I had discovered a secret door between this world and the dream world, and the secret knock that would open it.

Not all dream landscapes are relaxing, of course, and not all portals between worlds are safe to traverse.

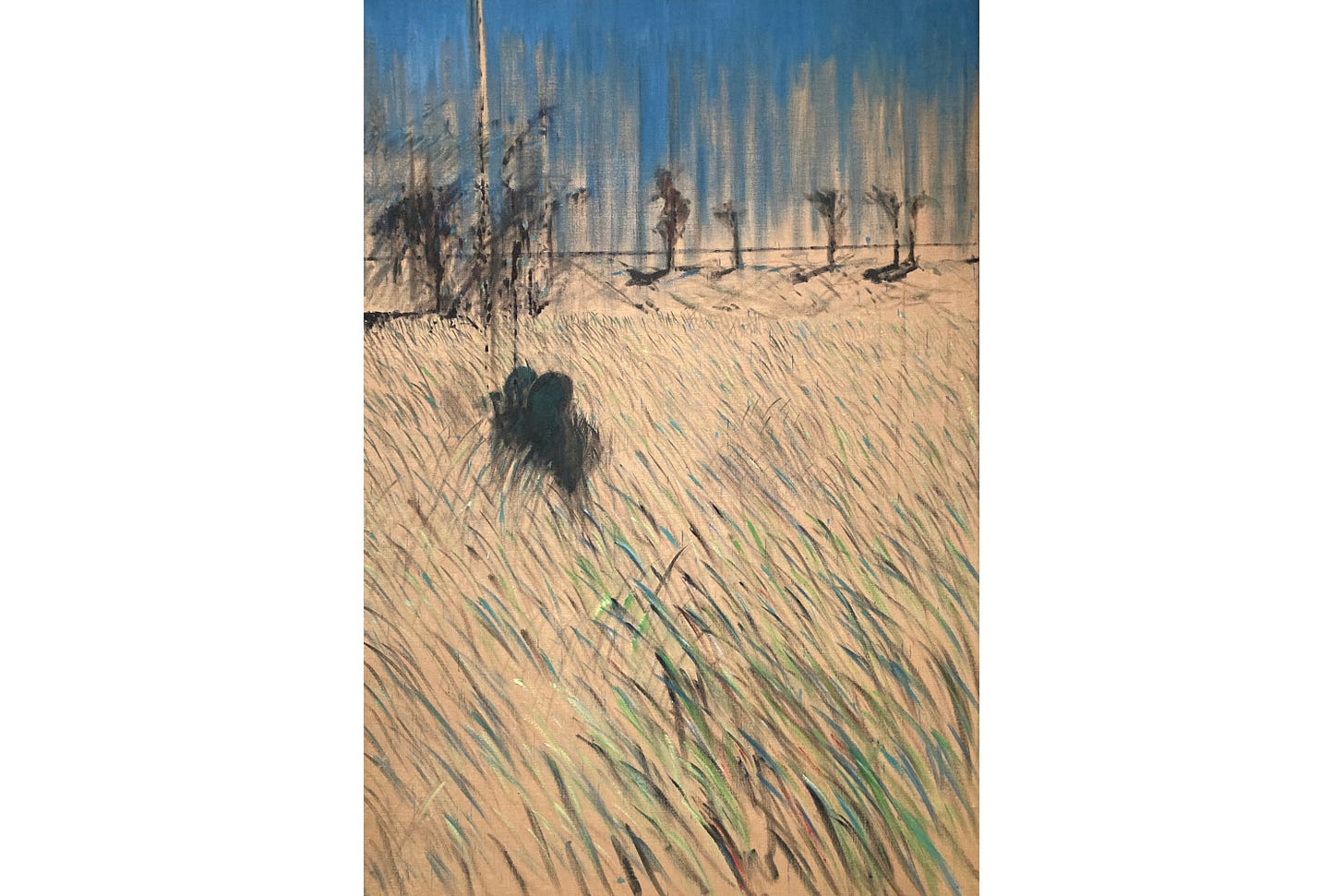

Francis Bacon’s Landscape depicts two figures coming towards the viewer through a field of grass. They are painted simply, nearly black geometric shapes just barely alluding to heads and shoulders, the rest of their bodies lost in the chest-high grass, the kind of grass that is difficult and somewhat terrifying to make your way through. The scene is made even more uncanny by the fact that the grass is rendered loosely as sharp spears of green and blue (and a little red) on an otherwise unpainted canvas, the lower part of the figures’ bodies literally dissolving into nothingness.

The grassland takes up the bottom third of the canvas; behind it are a row of tree-like shapes painted lightly in black; behind them is a thick and slightly uneven horizontal black line, which could just be a rendering of the horizon or could, given its unevenness, be a long mountain range in the far distance. The top of the painting is blue, but it is not a solid sky; the color rains down from the top, leaving portions of the “sky” as unpainted as the grasslands, and dripping down into the bare plains behind the trees.

The wall text tells us, “as in a dream, we strive to make meaning from this shifting and obscure vision,” but this is no dream I would wish to return to.

Over the years, especially after picturing myself in dreamlandia began to lose its efficacy, I have tried to deal with insomnia in a variety of ways. Improving my “sleep hygiene” — drinking less, less screen time in the evenings, etc. — has helped keep me from staying up too late, but made no appreciable difference to the frequency of middle-of-the-night waking. Breathing exercises, lying on my back, and getting up and journaling about my dreams (and only about my dreams) all initially seemed to promise, finally, a cure. But insomnia is a cunning adversary, quick to adapt to each new strategem employed against it. You don’t catch it napping twice, I guess.

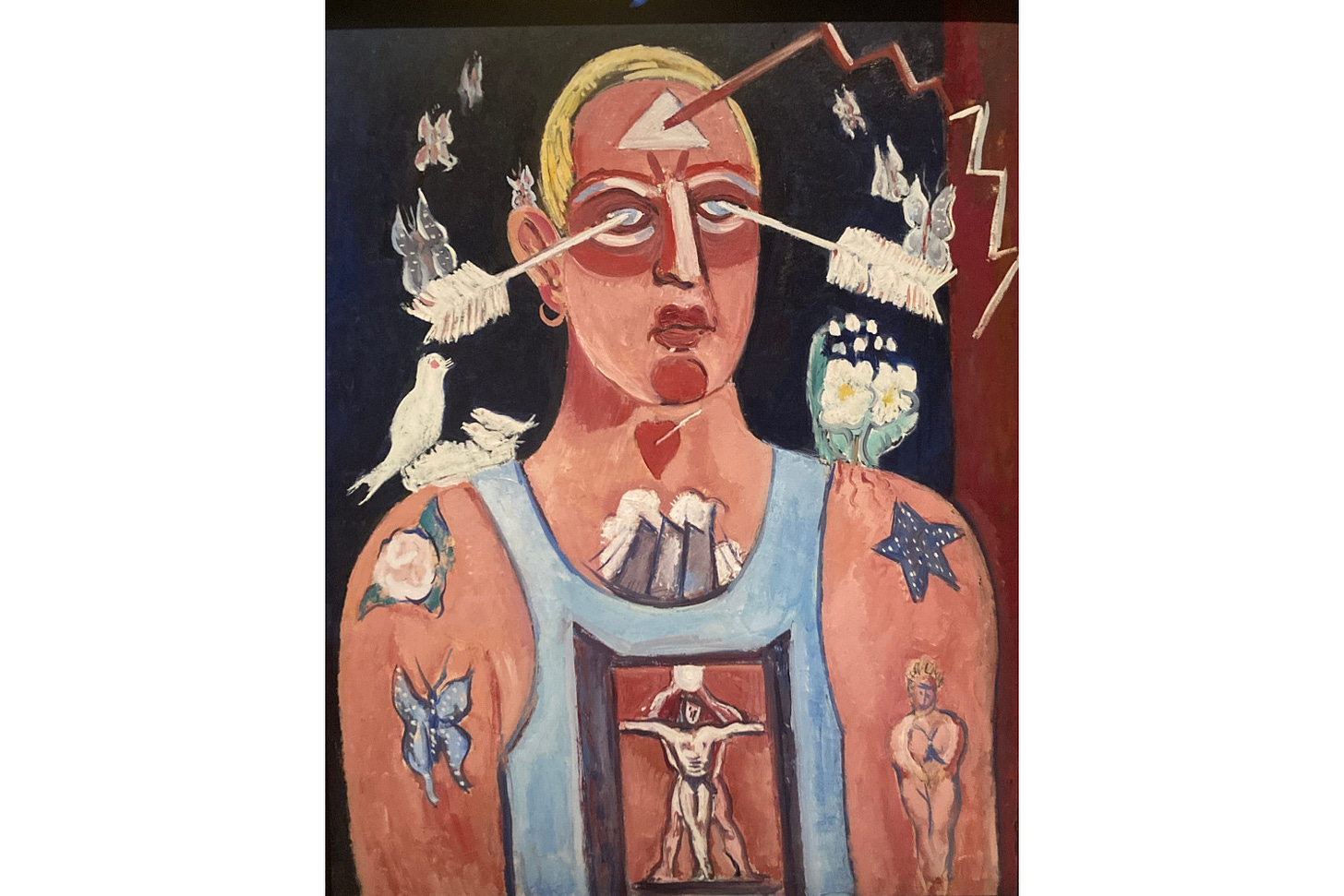

Marsden Hartley’s Sustained Comedy is a self-portrait of sorts, though you wouldn’t necessarily know that unless you read the wall text. Hartley, 62 at the time he painted it, depicts himself as “a young, tattooed sailor with bleached blond hair.” In addition to the tattoos on his arms and neck, there is a strange amalgam of a Christ figure and a body-builder that is either a tattoo on his chest or a figurine inside of it, revealed by a double door opening in the middle of his overalls. Two arrows pierce his eyes and a third, crooked one points at his forehead.

The wall text describes the painting’s “dream-like imagery, personal memories, and cryptic symbols,” and it definitely has the hallucinatory feel of a dream. But it also has the feel of insomnia, of restless rumination on the pains and pleasures that life has inscribed on our bodies, like a Facebook Memories feed plugged directly into our hippocampus.

Occasionally my insomnia is clearly because I have some leftover intense emotion from the day. Usually the emotion and its source are pretty clear — rage over some injustice, sadness over some tragedy, regret over some mistake — and simply giving myself permission to feel the intensity of the emotion, and let it pass over me and through me, allows me to get back to sleep. But sometimes it’s more complicated.

The better part of a decade ago, when I was reading a lot of self-help-adjacent works of pop psychology, I read a book actually called Permission to Feel. Written by Yale psychology professor Marc Brackett, it is, in its own subtitular words, about “the POWER of EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE to ACHIEVE WELL-BEING and SUCCESS.”

The style of the book is, to put it mildly, infuriatingly human-resources-y. Not just in the sense of advice to bosses on how to boss better and get more productivity out of their workers, though there is plenty of that, but also in the “children are our most valuable natural resource” sense. (As the folk singer Utah Phillips once retorted to that particular cliché, “have you seen what we do to our valuable natural resources?!?”) Brackett is a professor at Yale’s Child Study Center, and much of the book focuses on schools. It is written in that particularly irritating blend of lite social science and elite liberal-technocratic exhortation that is the hallmark of most writing on “school reform.” Needless to say, I was not a fan.

That said, when you are up in the middle of the night, and feeling all emotionally out of sorts, and not quite able to pinpoint why, Brackett’s suggestion that one learn to label emotions more precisely than “mad,” “glad,” and “sad” is, in fact, quite helpful. (This one of the keys steps — the “L” — in his “RULER” method.)

The other night I woke up around 2:40am, and could tell pretty quickly that it was going to be a big insomnia. I started thinking about an upcoming trip to Chicago in August and, while I did not descend into obsessive rumination, and was actually able to put the actual trip and the uncertainties related to it out of my mind pretty quickly, it left me with a sense of unease that would not let me sleep.

Lying on my back, doing my breathing exercises, I started teasing apart the knot of that unease. I couldn’t feel my way through the knot, but as I identified some of the components — anxiety, sadness, regret, hurt — I pushed myself to feel each in turn, as intensely as it demanded. As I did this, I felt the knot loosening, my body relaxing.

It’s hard to tell with these things, but I believe I was back asleep by 3:30 or so, and woke up feeling surprisingly refreshed.

Of all of the works in Night Poetry, the one that is most successful in creating a sense of “mystery and unease” for me — and in evoking and provoking complex, tangled emotions — is a 2002 oil painting by the Belgian painter Michaël Borremans. It is, along with Metamorphosis, my favorite work in the gallery.

It depicts three figures around a table. They are dark-haired and their skin is rendered as a kind of sickly dark beige. They wear nondescript work clothing which has clearly been bleached pure white but in the shadows is anything but bright.

Two of the figures, both women, seem to be moving their hands as if to measure or cut something on the greenish-brown table, but they hold no implements and the table is empty. The third figure, who is almost out of the picture in the lower left — all you can see are forearms and the forward fold of an apron — is holding something vaguely rectangular, perhaps a sponge or a sanding stone.

What first struck me when I first saw the painting, years ago, is that the full figure on the left seems to have a stump for a left hand, and her right hand is strangely misshapen — the back of the hand unusually elongated, the fingers short, stubby, and curled down like talons, even though they are not grasping anything. The figure on the right, too, seems to have only a thumb and a single finger on her left hand (though upon repeated viewing I realized it may just be the way her hand is angled obscures all of her fingers but the forefinger). I wondered if this was meant to be a depiction of survivors of some apocalypse, preparing to perform some dangerous medical or occult procedure in an underground bunker.

Looking at the wall text, I learned it is called The Lucky Ones, which was even more chilling — if these are the lucky ones, gathered with grim purpose in a dark and menacing chamber, what fate has befallen the unlucky?

Earlier this month I had a big insomnia on the night of the lunar eclipse, and instead of my usual practice of simply lying in bed, I got up, put on my coat, grabbed my camera and tripod and went outside to look at the “blood moon,” so called because during lunar eclipses the earth’s atmosphere refracts the sun’s light, bending the red rays into its own shadow and making the moon glow an eerie reddish color. (If the earth had no atmosphere, the moon would simply go dark during a lunar eclipse.)

My first proper crush was on the Greek moon goddess Artemis, Diana in the Roman pantheon, who is a hunter and the protector of wild nature. Unlike most Greek deities — especially her horndog father Zeus — she is unimpressed with the opposite sex, and is often known as the “virgin goddess.”

I rarely get out of bed while involuntarily awake, let alone go outside (or even look out the window), but I imagine that the moon must have been the companion to many insomniacs throughout history. The sun — who the Greeks deified as Apollo, Artemis’s twin brother, the most beautiful of the gods — demands our attention; we cannot live without it, and it shapes our lives in obvious and overwhelming ways. Like poetry, the moon works a more subtle magic; it is easy to be oblivious to.

During the eclipse’s totality, which began around 2:25am, it was high enough in the sky that it was largely unaffected by urban light pollution, and it was an unusually clear night. I cranked my zoom lens up to the maximum and took some photos, but then I turned off the camera and just stood there for a while, looking at something I had never seen before.

It still took me a frustratingly long time to fall back asleep after I went back inside. But maybe my body knows what it’s doing, at least sometimes.

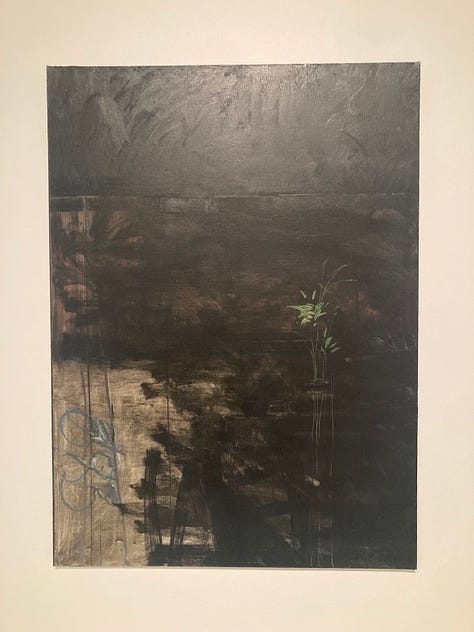

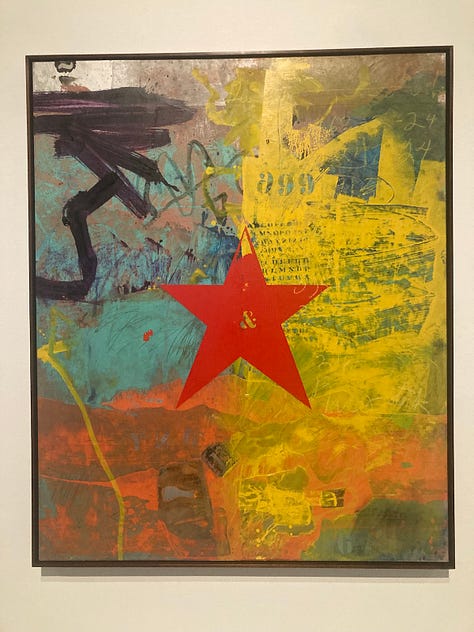

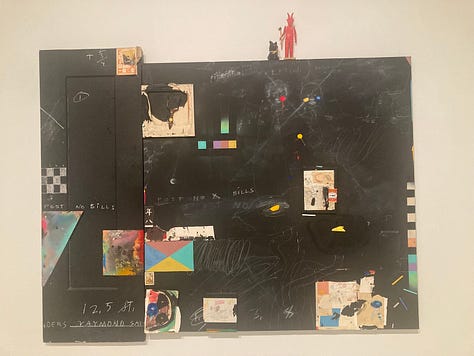

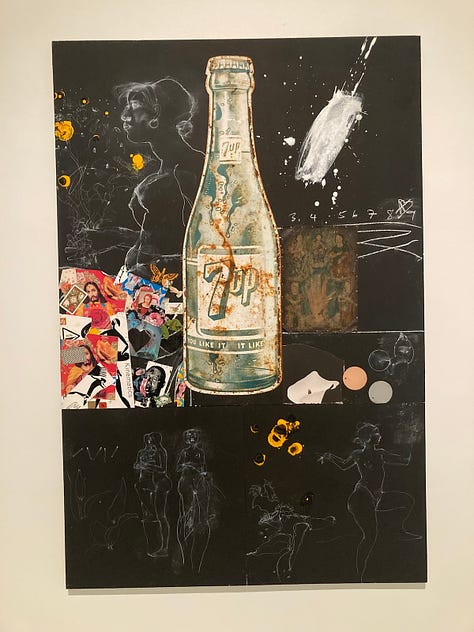

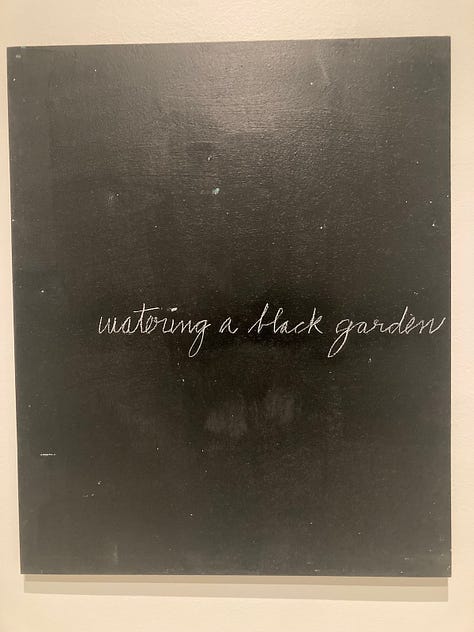

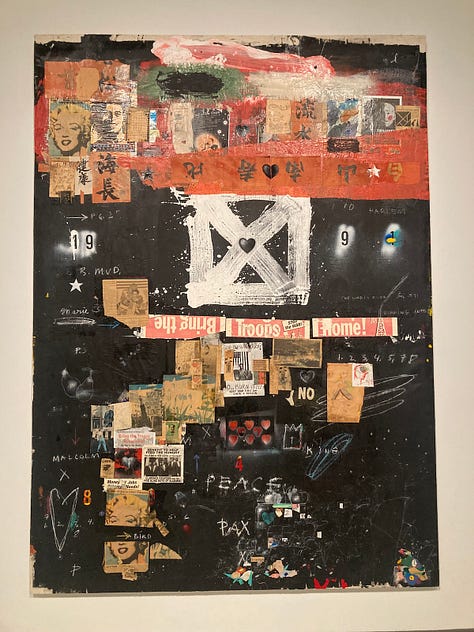

The Night Poetry gallery takes its name from a work by the artist Raymond Saunders, who was born and raised in Pittsburgh. His “first retrospective exhibition at a major American museum,” Flowers from a Black Garden, opened yesterday at the Carnegie Museum of Art. It is really, really good — definitely worth seeing — and I may write more about it in the coming weeks. For now, here are some pictures: